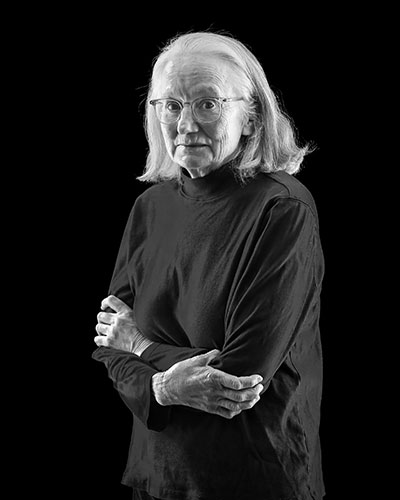

Melanie Roth | Photograph by Adam Williams

Overview: Melanie Roth is a historian who has been a huge part of historic preservation efforts in the Buena Vista, Colo., area, working on many projects during the past nearly 50 years.

She talks with Adam Williams about the history of St. Elmo, now known as a ghost town. One of the last full-time, year-round residents of St. Elmo was Melanie’s godmother, Annabelle Stark, who would go to town in October and buy enough food, beer and cigarettes to outlast the high alpine winter.

They talk about the 2002 fire in St. Elmo, how it got started, why it became the subject of national news reports that suggested it was due to a meth lab in the ghost town, and why she describes the seven outhouses that burned down, along with several buildings close to Melanie’s heart, as historic treasures. Among other things.

Or listen on: Spotify / Apple Podcasts

SHOW NOTES, LINKS, CREDITS & TRANSCRIPT

The We Are Chaffee podcast is supported by Chaffee County Public Health.

Along with being distributed on podcast listening platforms (e.g. Spotify, Apple), We Are Chaffee is broadcast weekly at 2 p.m. on Tuesdays, on KHEN 106.9 community radio FM in Salida, Colo.

Historic St. Elmo

Website: historicstelmo.org

We Are Chaffee Podcast

Website: wearechaffeepod.com

Instagram: instagram.com/wearechaffeepod

CREDITS

We Are Chaffee Host, Producer & Photographer: Adam Williams

We Are Chaffee Engineer: Jon Pray

We Are Chaffee Community Advocacy Coordinator: Lisa Martin

Director of Chaffee County Public Health and Environment: Andrea Carlstrom

TRANSCRIPT

Note: Transcripts are produced using an automated transcription app. Although it is largely accurate, minor errors inevitably exist.

[Intro music, guitar instrumental]

[00:00:11] Adam Williams: Welcome to the We Are Chaffee Podcast where we connect through conversations of community, humanness and well being in Chaffee County, Colorado. I’m Adam Williams.

Today I’m talking with Melanie Roth. Melanie is a historian. She has been a huge part of historic preservation efforts in our area, working on many projects during during the past nearly 50 years.

In this conversation, we especially talk about the history of St. Elmo, which is of particular love for Melanie. One of the last full time, year round residents of St. Elmo was Melanie’s godmother, Annabelle Stark.

We talk about Annabelle’s life, especially in St. Elmo, and how she influenced Melanie’s love of history. She would even study history and preservation at Tulane University in New Orleans. And while she was a college student, she would help to get the St. Elmo Historic District placed on the National Register of Historic places in the 1970s.

Melanie and I talk about the National Register, what it means and what it doesn’t. I was surprised at some of the things that I learned. We talk about the 2002 fire in St. Elmo, how it got started, why it became the subject of national news reports that suggested it was due to a meth lab in the ghost town, and why the seven outhouses that burned down, along with several buildings close to Melanie’s heart, were considered to be historic treasures.

The We Are Chaffee Podcast is supported by Chaffee County Public Health. Go to wearechaffeepod.com for all things related to this podcast, including transcripts, links and photos related to this episode and nearly 90 others in the archive.

Now, here we go with Melanie Roth.

[Transition music, guitar instrumental]

Adam Williams: I’m excited to talk about history with you, Melanie. My understanding is that you studied history and art history at Tulane University in New Orleans, is that right?

[00:02:10] Melanie Roth: That’s correct.

[00:02:11] Adam Williams: Okay. Well, you have brought that knowledge and so much experience to what you provide here locally for us. I know you are so integral to so many of the different historic aspects of where we live, whether that’s St. Elmo, it’s participating and even leading within the Heritage Museum. It’s so many projects, right. I don’t even think I can name them all. And hopefully we do at least get to bring some of them out in this conversation.

I want to start with if you remember, what was the first encounter for you with history? Something historical, something that really lit you up and made you think. I want to learn more about this.

[00:02:54] Melanie Roth: My family’s always had a very strong appreciation of history, just because my family was involved in so many things that are noteworthy. And so I always had that inherent appreciation. But I vividly remember going into staying with my grandmother at the home that she grew up in. And my cousin. We weren’t supposed to be doing this, but we went up in the attic and it was a walk up, walk in attic. And they had meticulously cared for all the objects that they no longer used that they wanted to keep. And they were carefully taken care of in boxes. And it was. It was like a conservator’s dream.

There were just incredible things that were 50, 75 years old that were so interesting to me as a child. So that really sparked my interest in museum objects and sharing that kind of history. And, you know, I have a fascination for older clothes and I have a great hat collection, clothing collection, all sorts of things. And I think it originated with my grandparents saving so many wonderful things.

[00:04:11] Adam Williams: How did they take care of things in a way that really stood out to you as kind of, like you said, conservatorship? Because that sounds very different than if you just go into a dusty, musty old attic where people just toss their stuff.

[00:04:25] Melanie Roth: Right. They took care of things with the intention of either reusing them or. Or passing them on to someone like that part of my family. All the women were, well, terrific seamstresses. But more than that, they were very artistic, and they made lots of hooked rugs and braided rugs, a lot of which ended up at a museum in Oklahoma. So there was just lots of wonderful material things that were going on. And they were. I try to impart this to my son and his friends.

You know, they grew up very much in the age where you saved every fragment of fabric because it was reused, re-sewn, and they had all had to survive the ups and downs of economy or their economic wherewithal. And so, you know, there was just a very much of an appreciation and a care, you know, because you might need something like that another day also.

[00:05:33] Adam Williams: Sure. If you’re talking about your grandparents, are we thinking, I mean, is this through the Depression, somewhere along the way, Dust Bowl? Because you mentioned noteworthy historic things. They’re in Oklahoma. That’s where you grew up, right?

[00:05:47] Melanie Roth: In all of my family, all sides. Or my grandmother that lived here in Buena Vista for good. But her advice was very terrific. Lifelong, when you move to an area, study and learn the history of that, because you learn who founded, who are the movers and shakers who kind of formed that area. And it will never be knowledge that you will regret having.

But my family, on my father’s side of the family, are Cherokee and also Scottish and German and English. And so they ended up early on in Oklahoma and were very involved with not only the Cherokee tribe before they left the Carolinas, but very much so in Oklahoma. Very, very involved.

[00:06:41] Adam Williams: Did you have family that was part of the Trail of Tears where they were force-marched from the east to Oklahoma?

[00:06:47] Melanie Roth: There were some, but there were also some that knew they saw the writing on the wall and they left prior to the Trail of Tears. But yes, of course.

[00:07:00] Adam Williams: So there are some really noteworthy things here that your family that you’re aware of with your knowledge of history that they have been involved in.

[00:07:08] Melanie Roth: Oh sure. Because they lost everything. And many families, whether they came westward and decided to start fresh again or they were forced to leave or economically, there was no choice for them. You know, you have an appreciation for things and what’s important in life if you’ve lost everything due to fire or whatever the circumstances are.

[00:07:35] Adam Williams: I’m thinking about Grapes of Wrath now too. In Steinbeck’s story of life during some of that period when people would have especially been losing things, would have had a lot of difficulty with security of livelihood and taking care of their families and would have been looking, moving to find opportunity, hopefully. But they would have been alongside so many other people that it still was such a dire thing. Something that feels so far removed from where we are now, right?

[00:08:02] Melanie Roth: For a lot of us, yes. And you know, the old joke in Oklahoma is during the Depression, the IQ of Oklahoma went up and so did it in California. But there were a tremendous amount of people that went to California and other areas because there just wasn’t the opportunity. Farming was gone, Right. In some areas.

[00:08:28] Adam Williams: When you went to college to study history, I wonder what you felt like your career path was going to be. Did you have a vision for what you wanted to do when with history, presumably after you graduated?

[00:08:40] Melanie Roth: I took as many historic preservation courses as I could at Tulane as a non architecture student. They didn’t offer any kind of historic preservation certification for non-architecture people at that point.

And so I knew I loved old buildings and I can go down the block in any city and I’ll pick out the worst looking one. And that’s my absolute favorite because it has so much integrity. It’s not been ruined over the years and remodeled and had the soul taken out of it.

[00:09:16] Adam Williams: So what kind of job did you end up getting after school?

[00:09:19] Melanie Roth: I tried and tried and tried to get a job with the state of Georgia. At that point I lived in Atlanta and I tried to get a job with the state in their historic preservation office and went through tons of interviews. And I was starving, so. And I was ending. I was selling clothes at that point. So I went into the brokerage business. So as a main way to survive.

[00:09:45] Adam Williams: Do you mean real estate or what?

[00:09:46] Melanie Roth: No, brokered stocks and bonds.

[00:09:48] Adam Williams: Gotcha. Okay.

[00:09:49] Melanie Roth: Yeah. And so that was. That was a wonderful avenue because I learned a tremendous amount and, you know, got my feet on the ground financially, and so that was terrific.

[00:10:00] Adam Williams: Do you consider yourself a historian?

[00:10:02] Melanie Roth: Yes. I’m not a professional one, but I’m.

[00:10:04] Adam Williams: Avocational, I think, meaning in the way of how you might describe yourself or think of yourself. Because this is such a deep love and passion, and you have done so much work here, as we’ll get to over the past, I think 35 years or so, have been very heavily involved in this. Obviously, you studied it. So if you didn’t become a professional one, it sounds like you had a different career path, but history continued to be a personal love and involvement for you.

[00:10:33] Melanie Roth: Right, because I’ve done tons of research work for pay. I mean, it’s not totally educational, I should say. Okay. But I. I don’t have a doctorate. I. And I wish I did. That’s one thing. I’m very sorry that I didn’t continue my education.

[00:10:49] Adam Williams: So to be a professor, or how would you use that?

[00:10:53] Melanie Roth: Oh, no, just in not teaching. I don’t. I. Or not teaching in a formalized classroom, but just. It gives you a lot more credence, and you have more of a train of thought on what portions of history are really important and what to kind of focus on.

[00:11:12] Adam Williams: Do you have any particular era when you talk about the clothes and things that you collect or the hats or just a particular area of interest in history, Is there something that you’re focused on?

[00:11:23] Melanie Roth: Well, I enjoy all of history, with the exception of, not a World War II fan.

[00:11:30] Adam Williams: Why is that?

[00:11:31] Melanie Roth: I don’t know. I just. I don’t like studying about death. And, you know, it’s interesting from the standpoint of where the generals were, you know, directing battles and from that standpoint. But I just. You know, I’m just very sorry about wars in general because lots of my family have died in wars, and so is everybody else’s. So if we can get beyond that at some point, I would be very grateful.

[00:11:59] Adam Williams: St. Elmo is a particular point of connection for you and your grandmother. Like you mentioned, she did live out here. Let’s talk about that history with St. Elmo. Because, of course, I. You know, I go up there from Time to time, I see what remains from its history, but I’m not really aware of it. And I feel like you are maybe the resident expert on that area up there, especially because you have some kind of family tie to who lived there.

[00:12:27] Melanie Roth: Saint Elmo is an absolute love of mine. When I was a little kid, my brother and I were too small to go on a tour of the Stark store. This was in the mid-1960s, and so we had to sit out on the boardwalk while everybody else went on a tour. And it made me so angry. I still remember that.

And so I have been totally enthralled with the area since then. My grandmother was a close friend of Tony and Annabelle Stark, and so I was the sixth child out of eight. And so my parents were running out of godparents at that point, and so I was privileged to have Annabelle Stark as a godmother, which was very interesting. She was raised a Catholic, and I think it was my grandmother’s way of seeing if she couldn’t steer her back into the Catholic, being a practicing Catholic, I guess.

[00:13:28] Adam Williams: Interesting.

[00:13:29] Melanie Roth: And so I’ve always been enamored. I met people, interviewed people that Annabelle knew from being all over the state of Colorado, and just sought to find out as much information as I could about her and the Stark family in St. Elmo.

[00:13:48] Adam Williams: Of course, I don’t have godparents, and I’m not familiar with what that relationship is or how it works. Did your parents have to find different godparents for each of you children? That’s how that works, yes. Interesting. Okay, so when she was your godmother, what kind of relationship then did you have with her?

[00:14:08] Melanie Roth: I was a very young child when she died. I believe I was only two. She passed away. But I read letters back and forth between my grandmother and her, and, you know, those are really exciting, you know, because she mentions me.

So even though, you know, we probably met, there was. I was just too young to have any kind of a major relationship, but godparents normally kind of, you know, they’re friends of the family, and depending upon how involved you are, you can have a strong relationship with the child and guide them, you know, conceivably through the Catholic faith and setting a good example or just being a mentor on many levels.

[00:14:57] Adam Williams: Do you feel like you missed out by the fact that your godmother was not able to be there for you since you were so young?

[00:15:05] Melanie Roth: No, no. She gave me a spark of interest in history in not only Saint Elmo, but Chaffee county and Colorado, that I would have never. I guess I would have found it eventually, but she really spurred me on.

[00:15:21] Adam Williams: So what was your relationship with her then, in terms of that kind of inspiration? And like you said, you. You went looking for kind of stories, it sounds like, and information about her. So even though she wasn’t physically present anymore, she clearly was an influence and part of your life. So how do you view that relationship in that sense?

[00:15:40] Melanie Roth: Well, she was an incredibly interesting person for the time. She was married to a railroad engineer. And there are all sorts of stories about the fact that they eloped and he was a Mason, which was a no, no if you were a Catholic. And her mother was very disapproving of that marriage. And so Annabel lived away from St. Elmo for a number of years, and she was involved in the insurance business and all sorts of things at a time this was like in the 1930s. And so she worked in Denver and lived in Trinidad and traveled a good bit around the country, which was very interesting because most people think, you know, when they go up to St. Elmo, they think those people stayed there and never went anywhere. And Annabel traveled extensively. So did her mother, so did her other brother. They had great lives beyond St. Elmo.

[00:16:46] Adam Williams: I’m curious, when you say he was a Mason, are we talking about, like, the Masonic– Are we talking about like the secretive whatever?

[00:16:53] Melanie Roth: Yes. Okay.

[00:16:54] Adam Williams: So that is something that I only know very, let’s say, through movies or TV shows. Like, it’s very much at the periphery of just kind of, for lack of a better word, pop culture in my mind. I don’t know what that really means. So where was the conflict in his being a Mason with what the mother thought the relationship should be?

[00:17:15] Melanie Roth: Well, the Masonic groups were, I believe, started in England, and George Washington was a Mason, as were a lot of other people. But their religious beliefs were, I’m probably going to get this wrong, fairly intolerant of Catholicism. So, okay, so there was the controversy there.

[00:17:38] Adam Williams: I need to learn about the Masons.

[00:17:40] Melanie Roth: Yeah. My mind is getting so old now.

[00:17:43] Adam Williams: It feels like this elusive but interesting sort of story that I don’t know. I need to go find what curtain that’s behind and take a peek. I actually watched a documentary on George Washington in the last week or two, and I don’t remember them referring to that in there at all. So that’s interesting.

[00:18:00] Melanie Roth: Yes, he was as well, as. If I’m not mistaken, there were other, you know, early people in our history that were as well.

[00:18:08] Adam Williams: So was this a religious driven thing?

[00:18:10] Melanie Roth: It was not quite Religious. But it was a secretive society essentially, and it was.

[00:18:19] Adam Williams: Which of course is the allure. That’s what makes me want to know, like what’s going on in there.

[00:18:24] Melanie Roth: Well, and you should be, because they’re just terrific buildings that are Masonic buildings. Like there’s one in Denver on Grant Street, I think that’s just incredibly cool. And one in Trinidad that everybody’s reworking.

[00:18:42] Adam Williams: So, okay, so back to Annabelle. She was. Along with. It was her brother. Tony was her brother, correct.

[00:18:49] Melanie Roth: Tony and Roy.

[00:18:52] Adam Williams: So they were among, if not the last to live in St. Elmo, at least during the winters, as I understand it. Is that true?

[00:19:00] Melanie Roth: Tony and Annabel were the last full time residents in St. Elmo. There were other people that were there during the summer, parts of the summer, but Annabelle and Tony lived there full time. Roy Stark, the other brother and his mother both passed away in 1943.

And so Annabelle and Tony from that point on, with the exception there was one man named John Anderson that was there for a while, I believe they were the only full time residents. And then can’t remember exactly when John Anderson passed away. But Annabelle and Tony were there by themselves.

[00:19:40] Adam Williams: What do you know about those stories of life, especially then during those winters, which I’m going to guess there was more snow or maybe something that made that harsher compared to what we have now, if for no other reason. The convenience of roads and vehicles and things that we have today compared to what they might have had access to then.

[00:20:00] Melanie Roth: Well, the snows obviously were much deeper and stayed much longer and it was much colder across the board. We just. In my lifetime, the difference that I have noticed in our climate is getting very drastic from what I remembered as a child. But Annabelle and Tony, excuse me, were living in St. Elmo without benefit of running water during the winter. They had electricity provided only by a generator. I find this totally intriguing. They would pack up the car and go to Salida in October to buy groceries to last through April.

[00:20:51] Adam Williams: That’s a big buy.

[00:20:53] Melanie Roth: And especially because they drank beer and Annabelle smoked cigarettes. And I cannot imagine, you know, having enough for that whole length of time. But after 1952, the road was closed or it was never plowed unless everybody got very concerned about the Starks because they were there at the end of the road in St. Elmo with it not being plowed. And that would be from, I believe, below Love Ranch. So it would be a huge hike, if you were an older person, to hike in the snow to come to town.

[00:21:34] Adam Williams: So do you know why they did that. Why did they choose to stay up there in isolation during those harsh conditions, only with each other?

[00:21:41] Melanie Roth: You know, they were protecting their property, first off, because there are tons of stories about Annabelle greeting people with a shotgun and asking them what they were doing, because people termed it as a ghost town. And it was a free for all and you could take whatever you wanted. And so they were. They were safeguarding. Um, and especially so because one of their summer neighbors, they had a. The Starks had a dog specifically, that they kept in the store because when they would leave, their neighbor would steal things. So they, you know, because they. They could have had another life somewhere else. But, you know, they. They worked hard for everything they had, and so it would be gone very quickly.

[00:22:31] Adam Williams: What work did they do?

[00:22:33] Melanie Roth: Well, they ran us. Tony ran the store in St. Elmo along with his brother Roy. And then they did mining, they did post office work, railroad. They rented cabins. They did all sorts of things to survive. They delivered groceries all the way into Taylor Park. In the 30s.

[00:22:57] Adam Williams: That would have been a rough go, wouldn’t it?

[00:22:59] Melanie Roth: Yes.

[00:23:00] Adam Williams: I mean, it still is a rough road if you were going to take a Jeep or something up there.

[00:23:04] Melanie Roth: Well, that road was in the 50s. I talked to lots of people in the 50s and 60s that would have taken their station wagons over it. That road has been totally destroyed.

[00:23:16] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:23:17] Melanie Roth: You know, with all the traffic, especially the recreational traffic, when it was just jeeps on those roads, there was very little damage done. But now there’s. All you have to do is go down a road after not being on it for two years, and it’s changed dramatically.

[00:23:38] Adam Williams: Is that from ATV use or ATV.

[00:23:40] Melanie Roth: And all the other ohv stuff.

[00:23:42] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:23:43] Melanie Roth: It’s just the way the tires are and the speed and the– You know, it’s a whole different– The Jeep parades that came through following World War II, you know, it was families and they were anxious to see what the countryside looked like, and they were stopping and investigating. And it’s a different mentality. I think now it’s like a giant amusement park.

[00:24:10] Adam Williams: Is it true that you were part of the effort to get St. Elmo placed on the national registry before your grandmother died in ’78?

[00:24:20] Melanie Roth: Yes. I was in college at that point, and I remember vividly going to the Colorado State Historical Society and saying, I would love to get this on the national register of this property. And someone else was already working on it, Doug Hagan, who’s an architect in Colorado outside Colorado Springs.

[00:24:41] Adam Williams: And–

[00:24:42] Melanie Roth: And so I helped with that endeavor. And Doug Hagan became A close friend of mine, and that was my first involvement with national register nominations or state register nominations. And I’ve been down that road many times with other buildings since then.

[00:25:01] Adam Williams: What does it take to have a building? Or in this case, are we talking about saying Elmo as a whole? All of the buildings.

[00:25:08] Melanie Roth: Yeah. It was listed as a district, which means that all those buildings kind of contribute to the time and. The time and the architecture that’s important to that area. And so there were originally, oh, gosh, over 40 buildings, and several of those have been lost to fire.

[00:25:32] Adam Williams: So what does it take to get something where. I mean, we’re talking about the federal government.

[00:25:37] Melanie Roth: Right.

[00:25:38] Adam Williams: To have somebody there approve what goes on to the register?

[00:25:41] Melanie Roth: Right. It goes through the national Park Service. And.

[00:25:44] Adam Williams: Okay, how do you persuade them that this is something that is worth noting? And I assume then that that brings some degree of protection, or is it just simply an acknowledgment where you get to put a plaque up and say, this is a value. This has historical meaning here?

[00:26:02] Melanie Roth: Okay, well, you have two questions there.

[00:26:05] Adam Williams: Okay, sure.

[00:26:06] Melanie Roth: One. One, you need to fairly do a fairly great job of doing the research on an area, what its history are the. What the people were that lived in that area or were associated with that building. And then you need to convey what is important. Is it architecture? Is it, you know, history related? Is it personal related? Is it what makes that so significant that it stands out in the United States?

And, you know, because there are tons of properties on the national register, but, you know, they’re. You just need to make a case for it. The lesser portion of that is the state register, which is administered by History Colorado and Denver.

And the requirements for listing are not quite as stringent as national, but in both cases, they offer perks of people being able to apply for grant funding here in Colorado and on a national level. But there are absolutely no requirements of how you take care of that building. You can demolish it. You can do whatever you want. There are no restrictions being listed on the state or national register. Where the restrictions come through is on a local level.

[00:27:32] Adam Williams: I think I’m confused by what you just said. That if you can tear it down, what is it that you are getting listed as saying, this matters. There’s historical value here. And then you can get grant funding, which can be applied in how you treat that property.

[00:27:51] Melanie Roth: Right. Well, if you received grant funding, that’s a whole different story. Then, you know, like from History Colorado, they have what are called easements that are placed on properties. If you Go over a certain dollar threshold. And so that property is protected just from the standpoint of the grants that you receive. But if you are on the national or state registers, there is absolutely no restrictions. A property owner can tear it down tomorrow. If you’ve received grant funding, that’s a whole different scenario.

[00:28:27] Adam Williams: Why bother to tear it down? Couldn’t you do that without bothering to go through the process of getting it noted on a registry?

[00:28:35] Melanie Roth: Normally, anybody that was interested in putting a property on the register would never tear it down.

[00:28:42] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:28:42] Melanie Roth: But I’m just, you know, like St. Elmo has been a listed register property, historic district property since 1979, up until the standpoint of when grants were given to certain of those buildings have every right in the world to just tear it down. And no one from history, Colorado, or on the national level came up and said, “you can’t paint it this color, you can’t do this.” There are no restrictions whatsoever.

[00:29:18] Adam Williams: That’s interesting, because that. That goes against what I would have assumed.

[00:29:23] Melanie Roth: Right.

[00:29:23] Adam Williams: It was about–

[00:29:24] Melanie Roth: And someone years ago started that misinformation being distributed probably as a means to protect something, you know, like a building they saved from demolition and saying that having it listed would protect it, and it doesn’t.

[00:29:42] Adam Williams: In essence, you’ve been involved, like you said, in many of these things since this process. For many of the properties and buildings that are here locally, there’s the Maxwell Schoolhouse, the depot, the drive-in theater, town hall.

[00:30:01] Melanie Roth: I don’t know that I got involved in a town hall, except for just as a consultant kind of a thing, just for information.

[00:30:10] Adam Williams: Okay. And I think there are others. Right. This is a very short list. So I guess, especially with what you were just suggesting, that there’s not necessarily those protections that I, and I assume, you know, millions of lay people like me would just assume, oh, this is on the registry. That means it’s protected. That means there’s all kinds of rules. Why is it important to get these things put onto the national registry?

[00:30:35] Melanie Roth: I think people don’t appreciate the history and the contributions of buildings until someone else recognizes that fact.

[00:30:44] Adam Williams: That’s a good point.

[00:30:45] Melanie Roth: Right? I mean, because, you know, a lot of people would say the Comanche is just, you know, it’s a drive in. But there’s so few drive-ins. In fact, I believe, gosh, There, I think four in Colorado now, and there are less than 50 still in the United States, I believe. And there are only, gosh, it’s less than five that are listed on the national register. So it is really a cool thing for Buena Vista to have that drive in.

[00:31:22] Adam Williams: I agree. I grew up with one in the little town I grew up in in northeast Missouri. We had one. Until years after I was gone, a tornado blew it down, and they did not rebuild.

So the ways that we can lose these little pieces, I mean. Well, big screen pieces of American history, I think are numerous. And the fact that they. I don’t know how many we had in the heyday of them, but there’s so few. I can’t believe there’s only 50 left across the country.

[00:31:53] Melanie Roth: I believe that’s correct.

[00:31:54] Adam Williams: Well, let’s say that’s just a ballpark number. I mean, that feels few to me. I won’t hold you exactly to 50.

[00:32:01] Melanie Roth: Oh, good. No, I would someone. I would gladly have someone correct me.

[00:32:07] Adam Williams: So let me ask what you might think is an absolutely ridiculous question. Why is history important? Why should any of us care about knowing our history and carrying that into the future?

[00:32:22] Melanie Roth: 1. You know, if you know your history, then you know not to repeat your mistakes.

[00:32:27] Adam Williams: But we do, don’t we?

[00:32:28] Melanie Roth: Well, because we’re not well versed enough on it. So.

[00:32:32] Adam Williams: Good point there, too. So I don’t disagree.

[00:32:35] Melanie Roth: Right. And it’s important to know where you’ve come from and why things have evolved the way they are. And, you know, for instance, why was Buena Vista set up the way it was? And that was because the people that laid out the town were doing it quickly because of mining and agriculture and the train coming through. And they were trying to attract a lot of investors quickly into the community. And so it was important for them to build structures right away, as was the case in a lot of other boom towns.

And just where the railroads went through and where the paths were, where the Indian trails were. The city of Atlanta, they’re, you know, Peachtree, everything under the sun. And they all go in squiggly lines and don’t follow any kind of path because they were based on cow trails. So you have to understand what the background is before you can understand a cow, a community.

[00:33:45] Adam Williams: You have Cherokee history and heritage in your family. Have you used your love of history to learn that piece of local history as well? Here, for the natives who were here prior to some of this building or all of this building.

[00:34:02] Melanie Roth: Right. I very much appreciate the natives that I’ve met in Colorado. Specifically, there is a Ute, Mountain Ute that has been involved in fostering more appreciation locally of Indian history. But I have not gotten on the scale where I should, should have. I’m just I have too many irons in the fire already. But I appreciate that, and I’m, you know, from behind the scenes, fostering what I can.

[00:34:36] Adam Williams: You had mentioned, if we go back to St. Elmo real quick, you had mentioned that some of the buildings have burned down. And I know that there was a fire a little more than 20 years ago, I believe in … 2002?

[00:34:45] Melanie Roth: Yes, it was in 2002.

[00:34:47] Adam Williams: And so I think that the town hall, the jail, there were some other structures that were burned down. How does a fire get started in a place like that that is, relatively speaking. I mean, it’s considered a ghost town. What kicks that off and then costs us that history?

[00:35:04] Melanie Roth: Well, it was a very, very, very sad fire. It was April 15th of 2002. There was electricity provided for the emergency radio that the county had, and the forest service made use of it, the county sheriff’s department, all that kind of thing. Because there were no landlines ever in St. Elmo after the demise of the city. I mean, they had overhead lines early on. So it was April 15, and it was a very strange year that I believe that was the same year as the Haman fire. Okay. So the conditions were extremely dry. There was very little snow on the ground. Where in Saint Elmo, where there should. Should have been feet.

The fire was caused either something to do with the radio itself or the electricity that was powering it. And it started at the town hall and then spread to a garage, a wooden garage that was built in the early 40s for Annabelle Stark for her model, model A car. And then also burned the Stark duplex, which between John Anderson, Tony and Roy Stark, they built that in 1910 and rented it out to people. Then it burned the Stark home, which was their original residence in St. Elmo. It was a frame two story and supposedly had housed the printing press originally for the Saint Elmo papers, the St. Elmo Mountaineer and the Rustler. And then also it burned two other things. One was a really nice log barn, two story log barn with a hayloft. And then a series of seven outhouses that were just treasures.

[00:37:12] Adam Williams: Why were those treasures?

[00:37:13] Melanie Roth: Well, I mean, normally people tear down outhouses, and these were totally intact. So it gave you a progression of time. And those had never, you know, they.

[00:37:24] Adam Williams: Because they would build a new one whenever they had filled whatever the pit was as far as they wanted to go. Okay. I’ve never thought about that or knew that.

[00:37:33] Melanie Roth: So it was the evolution of construction.

[00:37:36] Adam Williams: Sure.

[00:37:36] Melanie Roth: You know, because the. The very early outhouses were like. It’s like a barrel maker had a Heyday. Because they would line them with wood that was almost like tongue and groove. And then they spent a lot of time doing those. And then you could see how they didn’t care the longer it went through.

[00:38:04] Adam Williams: Interesting. I wonder why that was.

[00:38:06] Melanie Roth: Well, I think people just got tired, and they were hoping for a flush toilet eventually. But not to mention the archeology was important. But that was not, fortunately, not entirely lost.

[00:38:20] Adam Williams: It sounds like the buildings that were lost primarily were those that were related to your family in terms of, you know, your godmother and the connection there to your grandmother and their friendship. Of all the buildings there, you lost, the ones that kind of were closest to you in personal history.

[00:38:38] Melanie Roth: Yes, in a great– Because we had worked on everyone but one. The town hall belonged to the St. Elmo property, or they were the caretakers, the San Elmo property owners association. And then all the rest of them belonged to my family. And it was fortunate when that fire happened.

The sheriff’s department and the fire department had recently gone through meth training. As far as you know, that was the height of when meth was being produced in strange buildings places. And so when that fire happened, by the time it got to the Stark house, that was where the Starks housed all their linseed, their turpentine, and where the pack rats love to live.

And so the combination, those three items when the fire started produced a very memorable odor. And the fire department thought that it was a meth lab. So we went across the AP wire that St. Elmo ghost town lost a fire due to meth lab. But, you know, and. And we all just went, you know, great.

[00:39:56] Adam Williams: Sure. Yeah.

[00:39:57] Melanie Roth: You know, and I. I had some friends that were in Texas that were. Called me right away. They were just like, do you have a meth lab?

And I said, no, but so. And the benefit of that was that the state investigated that so closely because we were all terrified that it had been something like arson and that, you know, all the years of effort of everyone going down the drain because of an arsonist would have just been horrible. Remember, this is the Hayman fire, and–

[00:40:31] Adam Williams: Right. Well, and wildfire continues, of course, to be a risk. So are there any measures in place for that other than clearing defensible space and then hoping? Because that’s always a threat to everywhere out here.

[00:40:45] Melanie Roth: Right. St. Elmo and everybody in Upper Chalk Creek has been extremely forward in their thinking and actions as far as fire mitigation. And so if you look around the St. Elmo town site, there’s been a lot of work that’s been done. I mean, there have been thousands of trees taken out in the last few years because we have a high beetle kill, especially in Hancock. That whole area has just been decimated with pine beetles.

But so we take extreme caution as far as the conduct of what happens in the town. Site and property owners are very vigilant because besides, lightning campers are campers or inconsiderate people that are smoking cigarettes or leaving their campfires going.

[00:41:42] Adam Williams: With so many visitors, I think we get a lot of that behavior as well when they are not. It’s not front of mind to think about wildfires and how easy it could be for them to start one.

[00:41:51] Melanie Roth: Right. And it’s just. I mean, that’s all over, you know, in buena Vista. I mean, it could easily have a fire once the grass dries out. That could go quickly down through the valley.

[00:42:04] Adam Williams: I want to ask about those papers you mentioned in the printing press. You named two papers.

[00:42:11] Melanie Roth: I believe the initial paper was called the St. Elmo Rustler, and then it was changed to the St. Elmo Mountaineer.

[00:42:19] Adam Williams: Okay. Well, even to have one sounds amazing to me. And it makes me wonder who it was for or what the population might have been in the heyday of all the activity up there. Do you know anything about that piece of that history?

[00:42:33] Melanie Roth: Well, with any town that you’re trying to get on the map, essentially, the first thing you want to do is make it look bigger than it is. And that’s why you have all the false fronts and the wooden structures.

[00:42:46] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:42:47] Melanie Roth: You know, and you could. You could paint your sign on it, also your building sign. So they were really handy. Then the other thing you wanted to convey what was going on, and you wanted to really publicize the mining, the stores, they, whatever. And so newspapermen were sought after and could make a decent living initially in a community that they were trying to put on the map, essentially. And I was so anxious to finally read a copy of that newspaper because there are so few in existence. And I have to tout.

There was a gentleman in Kansas that had the foresight starting in the 1930s, to collect newspapers from all over in an effort to preserve those. And those were housed at the state historical society in Kansas. And they have, if I remember correctly, four copies of the St. Elmo Mountaineer paper that have since been digitized and are available widely now. But at the point in time in the 80s, when I got a copy of that, it was like gold, you know, And I was looking on oversized microfiche, and I was so saddened, because it was–

There wasn’t that much. I was hoping there would be tons of information about people in St. Elmo, but it was like, what’s going on in the world? Oh, interesting, you know, so they had gotten to that point, you know, where everybody wanted to know who, you know, where the Kaiser was and all this kind of stuff. And so it wasn’t as much local history where I’ve been able to get a ton of information about what was going on in St. Elmo and the whole Chalk Creek district is by reading the. All the Chaffee County papers.

[00:44:53] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:44:54] Melanie Roth: And I used to spend tons. I remember when I was helping out with the National Register nomination, I would spend a ton of time at the Buena Vista Public Library. And they had the roles at that point. And I really appreciate all the people that, you know, years ago, before Internet was available, did all their research at the libraries with microficher or going through a dusty library or a collection. It’s like Peter Anderson who wrote Gold to Go. That’s what he’s spent a whole winter doing, at least.

And then, I don’t know. You did not know June Chaputis, but she gave Chaffee county the biggest gift by researching where people were buried and what their histories were. And she did an index of all the known cemeteries and all that information. And she went through records at the courthouse as well as microfilm preservation sounds.

[00:46:02] Adam Williams: Like a key part of what you have been working on over the years, but I wonder about you as a writer as well. Are there books out there with your name on them?

[00:46:09] Melanie Roth: Not yet.

[00:46:10] Adam Williams: Well, and. Okay, that’s my next question yet. Okay. Are you going to write something? Is there something on your mind that you want to dive into, whether that’s St. Elmo or maybe something more comprehensive around this town?

[00:46:21] Melanie Roth: Oh, I have several. Several things that I would like to do on St. Elmo, and I just need to stop long enough to. To get focused on a project like that. Something I really. I have this editorial in my head that I’m really want to get on paper in Chaffee County. Because over the years, I’ve seen dramatic changes, as has anybody that’s lived in this area.

But I just want all the new people. And I’ve. I’ve gone. I try to meet as many of the new people in the county as I can because, you know, they obviously love it, just like all the rest of us do. And I almost feel like it’s my job to show them what history is in this community. And so they can understand it and have an appreciation for it, But I just know a lot of the old timers, it was a give and take to be able to live here.

You know, the salaries were not as good as in the big cities. You certainly couldn’t buy things that you could in the city. Your life was dramatically changed. And there were families that had made it to work since they first came. Like the. Some of the people that ended up in Winfield are still in this. In the county. And they have had several businesses. They’ve done all sorts of jobs to make it work.

And then you have– I don’t know. It’s interesting. There’s so much money in Chaffee county now. It’s a. It’s a whole different. Whole different framework from what the county was 30 years ago. And I just want people to appreciate that, you know, they’ve had many luxuries other places to understand how difficult it was for some of these families to hang on in this community. And so I’m a champion for all the old timers. In essence, in my mind, it certainly–

[00:48:35] Adam Williams: Was more difficult back then in many ways than it is now. And I think for an awful lot of people, it still is difficult in some similar ways to what you’re describing. People who are needing to figure out, how do I cobble together multiple jobs, how do I afford food and rent and all the things that. It’s a different way of difficult. But I think it still exists for many, many people who try to live here.

[00:48:59] Melanie Roth: Right. I mean, I just think back, you know, when I was a kid, there were few businesses and there were much fewer people. But I remember there would be people on Main street that would. During the height of the summer, they would put clothes. Gone fishing.

[00:49:20] Adam Williams: You know, just on any random day.

[00:49:22] Melanie Roth: Right. I mean, if the fish were biting, they were gone. And the same thing, you know, like, during hunting season and during all sorts of things. And so everybody understood in town because, you know, that was why everybody lived here, because, you know, they could earn a living and hopefully do what they loved.

[00:49:41] Adam Williams: Right.

[00:49:42] Melanie Roth: Okay. And then you had people from the outside that came in and said, oh, I want to start this business and that business. And so they were competing with all those people that had made it work forever.

And then it was like this giant wheel that went. Kept going because everybody wanted more business. So they advertised on the front Range, and it was this giant, giant, oh, I don’t know. Giant greed, for a better word, that was going on in this community.Whereas people had loved it and were totally endeared to it, and then it got very difficult to live here.

[00:50:26] Adam Williams: I’m curious about legacy. You’ve been involved in a few decades now of so much of this work with preservation. As a historian involved in educating those who come behind you, do you think at all about what your place is maybe in this history of these past few decades, as that continues to move forward, and how you have been part of preserving some of these buildings that, you know, who knows how long they’re going to stand in part because of your efforts?

[00:51:03] Melanie Roth: Well, I hope through all the national and state register listings and just the promotion of historic resources in the county that people will think twice before they come through with redevelopment or something. Because our.

Our heritage and our culture is extremely important. It’s who we are. And if you take that away, it’s downtown Denver, you know, it’s some Denver suburb, or, heaven forbid, it’s downtown Breckenridge. I mean, so there’s a valid history, and I hope that stays forever because that’s what I loved about Buena Vista. And then the new wave with the, you know, all the water activity in the county, I mean, that has its own history and its own following, and, you know, that’s important to preserve as well. It all kind of fits in and makes Buena Vista what it is.

[00:52:07] Adam Williams: Change is inevitable. Evolution, perhaps, then is inevitable. And keeping track of what that history and the evolution of that in the story, I think is worthwhile and to allow space for that evolution rather than say, we’re going to try to fight change, all we want was whatever. In my mind, I think that golden era was.

You know, there’s– There was history. You know, we referred to the indigenous peoples who are here before any of this. We are part of that change and it’s perpetual.

[00:52:38] Melanie Roth: Right. I mean, I kind of like in the old timers and BB, you know, really have an appreciation for what the Utes and all the other Indian tribes went through. You know, they– You couldn’t stop it. You might as well join the. Join the parade or you’ll be run over. So, yes, we just need to work harder about appreciating those factors in groups that contributed toward the history of the area.

[00:53:06] Adam Williams: Melanie, thank you for everything that you’re doing around here. That works toward that end. Thank you for coming on here and sharing, and I’ve learned some things along the way in this conversation, so I appreciate this time with you.

[00:53:17] Melanie Roth: Oh, well, great. Well, you just have to come up for a cobweb tour.

[00:53:21] Adam Williams: Absolutely.

[00:53:22] Melanie Roth: Yes.

[00:53:22] Adam Williams: That sounds like fun.

[00:53:23] Melanie Roth: It is. Because I always tease everybody. I mean, it’s Cobweb Tour. It’s not what everybody gets to do all day in St. Elmo.

But also you can clean one day and the next day they’re cobwebs. So you’re helping. You’re tall, so you can help really clean the cobwebs out.

[00:53:39] Adam Williams: Sounds good.

[Transition music, guitar instrumental]

Thank you for listening to the We Are Chaffee podcast. You can learn more about this episode and others in the show notes@wearechaffeepod.com and on Instagram @wearechaffeepod. I invite you to rate and review the podcast on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. I also welcome your telling others about the We Are Chaffee podcast. Help us to keep growing community and connection through conversation.

The We Are Chaffee Podcast is supported by Chaffee County Public Health. Thank you to Andrea Carlstrom, Director of Chaffee County Public Health and Environment, and to Lisa Martin, Community Advocacy Coordinator for the larger We Are Chaffee Storytelling initiative. Once again, I’m Adam Williams, host, producer and photographer for the We Are Chaffee podcast. Till the next episode, as we say at We Are Chaffee, “share stories, make change.”

[Outro music, horns and guitar instrumental]