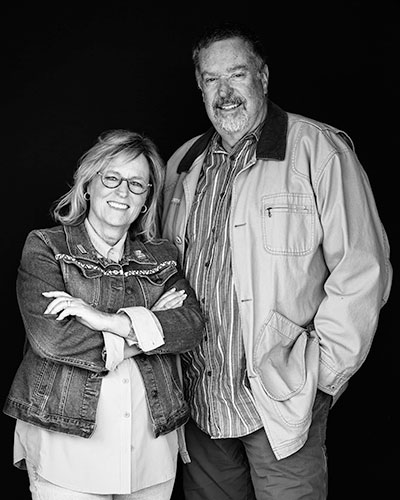

John & Coleen Graybill | Photograph by Adam Williams

Overview: John and Coleen Graybill, of the Curtis Legacy Foundation, are doing their “life’s best work” in retirement. Through the Foundation, they are focused on raising awareness of indigenous peoples and their cultures. They use the iconic work of Edward Curtis, John’s great-grandfather, to do that.

They talk with host Adam Williams about their own lives in photography, as well as Curtis’ life more than a century ago and his 30-something years of documenting dozens and dozens of Native tribes in North America. They also talk about how they are extending that work through their Descendants Project today. Among other things.

Or listen on: Spotify / Apple Podcasts

SHOW NOTES, LINKS, CREDITS & TRANSCRIPT

The We Are Chaffee podcast is supported by Chaffee County Public Health.

Along with being distributed on podcast listening platforms (e.g. Spotify, Apple), We Are Chaffee is broadcast weekly at 2 p.m. on Tuesdays, on KHEN 106.9 community radio FM in Salida, Colo.

John & Coleen Graybill | Curtis Legacy Foundation

Website: curtislegacyfoundation.org

YouTube: youtube.com/@CurtisLegacyFoundation

Instagram:.instagram.com/curtislegacyfoundation

Facebook: facebook.com/CurtisLegacyFoundation

We Are Chaffee Podcast

Website: weareChaffeepod.com

Instagram: instagram.com/wearechaffeepod

CREDITS

We Are Chaffee Host, Producer & Photographer: Adam Williams

We Are Chaffee Engineer: Jon Pray

We Are Chaffee Community Advocacy Coordinator: Lisa Martin

Director of Chaffee County Public Health and Environment: Andrea Carlstrom

TRANSCRIPT

Note: Transcripts are produced using an automated transcription app. Although it is largely accurate, minor errors inevitably exist.

[Intro music, guitar instrumental]

[00:00:13] Adam Williams: Welcome to the We Are Chaffee Podcast, where we connect through conversations of community, humanness and well being. In Chaffee County, Colorado. I’m Adam Williams.

Today I’m talking with John and Coleen Graybill of the Curtis Legacy Foundation. The foundation is focused on raising awareness of Indigenous peoples and their cultures, and it’s the work of Edward Curtis that provides such an incredible doorway for doing that.

Maybe you recognize Edward Curtis name. Even if you don’t, it is almost certain that you have seen his photographic work somewhere. History books, framed artwork displayed in museums or art galleries, or of course, millions of places on the Internet.

John is the great grandson of Edward Curtis, the photographer who is renowned for his decades of work documenting Native tribes in North America beginning in the late 1800s.

I talk with John and Coleen about Curtis’s life and his photography, but also learn along the way that Curtis published 20 volumes containing anthropological writing and stories from his 30 something years spent with dozens and dozens of Indigenous tribes. And all of this at a time when the American government still was bent on seeing them as savages who were less than. Now those anthropological writings are being used by Native tribes today to reconnect to their past.

Coleen and John are both portrait photographers themselves, so we talk about their lives in photography too, and how besides being keepers of the flame for Curtis iconic body of work, they are extending it in some fascinating ways.

We talk about their descendants project, which has led to John making his own collection of portraits photographing descendants of those who were photographed by his great grandfather a century ago, give or take. They also interview descendants and collect their stories on video.

We talk about Coleen’s efforts overseeing publication of Curtis’s previously unpublished works too, among other things, like the dark period of decades in the 20th century when Curtis’s work was forgotten in a Boston basement and what happened after it was found there.

The We Are Chaffee Podcast is supported by Chaffee County Public health. Go to weareChaffeepod.com for all things related to this podcast, including links to the Curtis Legacy Foundation’s projects, videos and books in this episode’s show notes.

Now here we go with John and Coleen Graybill.

[Transition music, guitar instrumental]

Adam Williams: John, you’re a descendant of Edward Curtis. He was your great grandfather and I’m fascinated by this. I have known of Edward Curtis for many, many years, but I also think that might be because I have a background in photography and I don’t know if that colors my perception of how widely known his story is or his work.

So I’d like to get your take and we kind of set the table with this. If you’re sitting on an airplane and a stranger next to you, somehow, you know, it comes up. They learn you’re the great grandson of Edward Curtis and you have this work you do with the Curtis Legacy Foundation.

Are they more likely to recognize his name and you see their eyes light up, or are they more likely to say “who?” And then you have to explain.

[00:03:39] John Graybill: This happens all the time. It truly does. And what I find most often is people recognize the images, but they don’t know who the artist was.

It’s probably the most common. So then it goes into the whole discussion. Well, Edward Curtis photographed this, and he did all this work with Native Americans from 1895 to 1930. And then that opens up the whole other discussion.

And part of what is unsettling for me, knowing the work so well, is how everybody always looks at his photographs. They’ve seen those, they’re all over the place. But there’s very little awareness of the 20 volumes of text that he wrote that the pictures support.

And that’s where the conversation can get going pretty good, is start talking about the text and all the information that he captured about these people.

[00:04:38] Adam Williams: I think we’re going to get into that. I hope so, because I do want to learn about that. And I’d have to admit that even though I just said I’ve known of him and his photography work for many, many years, this is news to me that he wrote so I would say prolifically in whatever it was he was documenting.

So I do want to hear about that. But if we can elaborate first so we don’t leave anybody behind who might be listening. And they’re saying, I don’t know if I know who Edward Curtis is. I’m not sure if I know his work. How do you explain to people, how about we go into a little bit more depth about who he was, what he was doing?

[00:05:10] John Graybill: Why, sure, he had an interesting start. Son of a preacher who was in the Civil War, Johnson Curtis. And he came back from the war pretty sickly. And so Curtis, not the oldest, but maybe the most appropriate in the family to support the family, did all kinds of odd jobs all his life.

And I think the one significant one was he did a photo apprenticeship in a St. Paul studio. So that’s where his photography background initially started. And the families living up there, they have a really hard spring that kills most of their crops that they had planted.

They’re dirt poor. You know, they literally. They have no money. Johnson’s not really working. And so they decide that they need to leave the Minnesota area and they go to Washington territory, out to Sydney, Washington, which is on the Olympic Peninsula.

Later, once Washington territory becomes a state, they rename that Sydney Port Orchard. Port Orchard. Thanks, honey. To Port Orchard, Washington. So he and his dad, they go out there, they hand build a cabin from logs. They’re basically homesteading. So they’ve got a plot of, I don’t know, 160some acres.

They build this cabin, they plant fruit trees and all kinds of stuff. And they send word to the rest of the family to come join them in Washington. And they do. Everybody except the older brother, Raphael, he stays back and so they all come down there. Three days after the family arrives for this grand reunion in Sydney, Johnson Curtis passes away of pneumonia. And so Edward and his brother Aishol are thrust into supporting the family yet again. And they’re doing all kinds of odd jobs. And one of the jobs that Curtis does is working for a logging company.

And he has a bad fall and injures his back. And that lays him up for almost a year in the cabin, you know, and all he’s doing is looking out the window. And we think that that may have stimulated some of his photography. Watching how the light changed from sunrise to sunset and all the changes that had happened during the day.

And one of the neighbor girls, Clara Phillips, who was a very young teenager at the time, starts helping Edward’s mom take care of Edward and they nurse him back to health. And after a year he’s up and out of bed and doing stuff, but he realizes he can’t do that kind of physical labor anymore. And so he leans back on the apprenticeship in St. Paul with photography. And he builds a camera with a lens that his dad had brought back to him during the Civil War and some instructions out of one of the photography magazines at the time.

And so he does this. He buys into a studio in downtown Seattle. He like mortgages the property. Everybody thought his mom was nuts for letting him do this. She didn’t really approve of it, she thought it was a waste. But he becomes a very successful portrait photographer in Seattle for like the well.

[00:08:45] Adam Williams: To do families or. Who would this have been for at the time?

[00:08:48] John Graybill: Well, probably mostly the upper white colonial people that had moved in.

[00:08:55] Adam Williams: Which of course is not what he ultimately ends up being known for.

[00:08:58] John Graybill: Absolutely. And so he does all this photography. I mean, he’s got people lined up and he’s known for if you want a portrait done, this is where you go.

And so I think he gets bored. And grandma, my grandmother Florence, his Third child writes in one of her books the same thing, that her dad got bored doing that. So he starts venturing out. He starts climbing mountains like Mount Rainier and some other ones, St. Helens in the area, and becomes quite the mountaineer. And he also takes his camera down onto the shoreline, the Seattle shoreline, photographing some of the natives that are still out there picking mussels, digging clams, whatever the activity was. He starts photographing them.

And something in that sparks with him. And I think probably one of the more significant individuals that he photographs is Princess Angeline, who is the oldest daughter of Chief Seattle. And she’s still allowed to wander the streets, kind of. She’s like the only one, because they’ve got laws against doing that.

[00:10:08] Adam Williams: You mean for Native folks?

[00:10:09] John Graybill: For Native folks, yeah. Ordinance five, I think about the mid-1800s, prohibited natives from walking the streets downtown, their homeland, unless they were accompanied by some white people.

And it’s hard to imagine this is their homeland and they’re not allowed to live there, and they just get pushed out of the city. Except for Princess Angeline. He offers her a dollar to come up to the studio and sit for a portrait. And so she does that. She thinks it’s great. That’s better than digging clams, picking mussels, doing laundry for the Maynard family.

And so that was his first Native portrait that he did. He’s venturing up to Tulala up north of Seattle, the tribe up there on their reservation. He’s photographing them. We’ve got evidence as early as 1895 that he was doing this. And we think this is where the passion started.

[00:11:07] Adam Williams: So he does become known for his portraiture. And I guess. Are we saying documentation of some sort of Native tribes of indigenous people throughout North America?

[00:11:20] John Graybill: Well, early on, he had. And I guess a lot of studios had this. They had what they called the Indian corner in the studio.

And so he was all decorated with rugs, pottery, and photos that he had taken. And it was a profit center for him from the studio. He would sell the pictures that he was making of natives.

[00:11:41] Adam Williams: He would have them come into sort of what we might think of as a kitschy setup that would kind of present them in the way that white Americans might already think of them. Is that what we’re saying?

[00:11:51] Coleen Graybill: No, it was at that point, it was either out on the beach, you know, more of an environmental portrait, or journalism, you know, something that was outdoors and it was interactive. As far as coming into the studio, if he did that, he just used a plain, solid background.

He didn’t use the painted European pillars and big floral arrangements. And he didn’t do that. He didn’t try and colonize the photo of them, as far as I’m concerned, with props and backgrounds like a lot of other photographers did.

[00:12:31] Adam Williams: Right. Okay.

When he would start traveling and doing this, my understanding is he spent 30 plus years. And this is what he’s really known for. Right. Is is this photography that ultimately ends up documenting what the white American government is trying to do away with by removing indigenous peoples and tribes from their lands, by colonizing all of these things. And he is documenting from the late 1800s into the early 1900s.

What was his reason, as you understand it, for that? Why did he care about it?

[00:13:09] John Graybill: The best we can tell, and sadly, he didn’t keep a journal or a log or anything to tell us what exactly was going through his head at that time. But from the evidence that we found, it appears as he got to know these native people, he really had a deep appreciation for their culture and their religion.

And I believe personally that that was the motivation. He found something unique in these people that he fell in love with. And you look at the photos that he did, different from people doing documentary type work where it’s like a scientific documentary. He was doing beautiful portrait work of these people and he tried to make them look the best he could with what he had.

[00:14:00] Adam Williams: Was he trying to celebrate them, like hold, hold them up in a positive light when otherwise they might have been shown?

[00:14:06] Coleen Graybill: Absolutely.

[00:14:06] Adam Williams: In some sort of impoverished or heathen-type state?

[00:14:10] John Graybill: Yeah. As you got to remember back in that time, our government was preaching that these were savages, they had no religion, they had no culture, when actually their culture and religion was probably more structured and deeper than the white culture that had moved into the area.

[00:14:28] Coleen Graybill: One of his more famous quoted remarks from him was, I want to make them live forever. So he wanted to educate people. He wanted to lift up and make people see that they’re human beings just like the rest of us.

[00:14:49] Adam Williams: I wonder how that went over with, let’s say, higher society like JP Morgan, who would become a patron of his essentially right and pay for these things. He paid, I assume, for the travels and maybe paid for the rights to the work he was creating. How did that go?

[00:15:06] Coleen Graybill: He was very much about railroads and the steel, and that was a big push for moving all these native indigenous areas, moving those people out of the way of the railroads. And he wasn’t necessarily sad about that. Why did he so then to see him back Curtis’s project so fully, I don’t know.

[00:15:37] John Graybill: Morgan did have quite a rare book collection. That was one of his things. So he was into collecting art. So Morgan had an appreciation for art and books that kind of played into what Curtis was trying to do with the project.

[00:15:53] Coleen Graybill: There were some turning points during that time, too, because Roosevelt, Teddy Roosevelt, was that way too. He was known to say, the only good Indian is a dead Indian, and things of that nature. Kill the Indian, saved the man.

You know, those kind of quotes. And. And then when Curtis started his project and Teddy became president, there seemed to be this big turn of supporting what Curtis was doing and preserving that history.

[00:16:25] Adam Williams: So that brings me back around my question that I started and then I derailed myself to J.P. Morgan. But it was, how were people receiving what Edward Curtis was doing as a white man? He was out here documenting and presenting them in such a, you know, humane and beautiful ways. He was trying to show the positive and the light in these people.

And I wondered how that that was received if he was a man with no home, basically, because if white people are mad at him for doing this. But also a second question for me is, how did he even build rapport to come into these tribes, of which I understand there are around 80 or so he ultimately would get to know and work with. I just loaded up a bunch of thoughts there.

[00:17:07] Coleen Graybill: You did.

[00:17:07] John Graybill: It’s like, where do I start with that?

[00:17:10] Adam Williams: We can bundle the thoughts a little bit. How was he received in his work?

[00:17:16] John Graybill: You know, early on, if you can get into the mindset, “the only good Indian’s a dead Indian. Save the man. They have no culture. They’re savages.”

And it was the arrogance of the colonization that was occurring at that time that thought were superior, that the whites are superior. You know, the Industrial Revolution is just manifest destiny. Manifest destiny. The Industrial Revolution back East, colonists thought they were all that. And they see these people, you know, living in teepees or whatever kind of shelter that they had made.

And people were fascinated with this. Curtis was bringing into their homes a glimpse of what they were, what they looked like, and what the government was trying to get rid of. And I think people were just fascinated by his images. And so they appreciated the pictures and the work that he was doing.

[00:18:18] Adam Williams: From afar.

[00:18:19] John Graybill: From afar.

[00:18:19] Adam Williams: They would not have wanted to have to mix it up themselves out in, you know, with this arduous travel and the rough conditions in the West. That’s dangerous. But if he was willing to do it, I’ll pay for the art, kind of.

[00:18:32] John Graybill: Yes.

[00:18:33] Coleen Graybill: They would never think of walking into a native village Which Curtis sent many times. He’d send an interpreter ahead who was native and. Or contact with the Indian Bureau and let them know that he always had to have kind of approval from the governmental, you know, people for him to go in there. But I think the interpreters helped tremendously in going ahead and explaining what he was doing, why he was doing it, and what the results would be.

[00:19:08] Adam Williams: I wonder if he would send along portraits to show. I have photographed. I have this portrait of this princess I have now. You know, as the body of work continues to grow, it’s what we would do now in the same way with a documentary project with a community of people that you are an outsider to, you would try to slowly make inroads, to build trust and have them see the work you’re doing, see what your intentions are.

[00:19:33] Coleen Graybill: Yes. There are a couple writings where I’ve seen someone mentioned he brought us photographs or brought back photographs that he had taken. That was after the fact, but I’m sure he did that. And he did develop some out in.

[00:19:54] Adam Williams: The field to show them in reasonable, real time.

[00:19:58] John Graybill: Yeah, yeah, he was doing cyanotypes out in the field, you know, so he would have to process his negatives in the field and then during the day, do the cyanotypes.

Those are really rare. If you can get a hold of those, they’re. They’re kind of crazy. But we. At least I like to think that he was able to show people in the moment that picture that he had taken through a cyanotype.

[00:20:22] Adam Williams: Turn his iPhone to him and show him what he just got.

[00:20:24] John Graybill: Right.

[00:20:25] Adam Williams: My understanding is that he ultimately would make around 40,000 portraits, or not necessarily portraits, but photographic images. So that. That could have been inclusive of portraits and all kinds of other things. Is that number reasonably accurate to your understanding?

[00:20:41] John Graybill: You know, my. My Uncle Hal uses that. That number. And we’ve got him on audio tape from the early 80s talking in interviews, where he gives that number that obviously that number is rounded from what we don’t know. And sometimes I like to think, well, that was the inventory that they purchased for, you know, his supplies. They purchased 40,000 names. I don’t know. We have no record of it. That’s just my personal thought. But, yes, he photographed a ton of stuff.

And even with the North American Indian Project, through his negative log book, which I’ve determined mostly is a catalog of images that he might use in the project, it’s a little over 5,000.

And then there’s all the stuff that wasn’t used that’s in there. Which is what gets the Centaur unpublished series. So we. We don’t know the exact number that he actually photographed. Probably somewhere around there, possibly.

[00:21:47] Adam Williams: Does that feel prolific to you, given your knowledge of the techniques he was using, you know, the technology of the day and what he was having to do. And I’m thinking everything took longer, not only to see the image, but it’s also that travel again. I’m thinking of traveling through the west when there were no interstates, you know, he. And developing these relationships with the communities. I don’t know how long he would spend in any one place, but it just seems like for this, 30 years or so that he was doing this.

Everything is slowed down in what every effort takes. And yet he still had however many, let’s say tens of thousands of these images that he made. Seems amazing, like such a body of work and legacy to leave behind.

[00:22:36] John Graybill: Absolutely. You know, I want to circle back on a comment that we talked about earlier before I lose it. And that is when he would go into these communities, these Native communities to do his work, and Coleen touched on it, that an interpreter would go in front of him. And early on he had the privilege of having a Crow native work with him by name of Alexander Upshaw. And Upshaw was a graduate of the Carlisle School for Indians.

So he’d gone through the process where they tried to kill the Indian and save the man, you know, and there’s pictures of Alexander in a button down shirt with a tie, extremely intelligent, well educated through all that. And he would go in, in front of Curtis maybe several weeks and just get the tribe ready for what was going to happen when Curtis got there and what to expect.

And then when Curtis would get there, he would spend some time getting to know the natives too. You wouldn’t just set up his portrait tent and start photographing. He would take time. And from what best we can understand, he would go in, spend some time with them, help gather water, food, firewood, whatever it might be. And as they started to become more comfortable with them, then he would start doing this work. He didn’t force anybody to do the portraits. It was anybody that was. Wanted to do it based on what they were learning about Curtis from Upshaw.

[00:24:07] Adam Williams: And so forth at this point. Was it all voluntary in the sense of they could see that he was working on something of. Of value and meaning that was, you know, not just about.

Well, what I’m thinking is how he paid the princess in Seattle a dollar. Was he paying others to participate all along the way or were they voluntarily, say collaborating in some sense, in this project.

[00:24:36] John Graybill: Now, he, best we can tell, he paid them all. And he would travel with sacks of silver coins.

[00:24:43] Adam Williams: Wow.

[00:24:43] John Graybill: Sacks of them. And this comes into play later on. He’s in Canyon De Chelly and his son.

[00:24:49] Coleen Graybill: Which is in Arizona.

[00:24:50] John Graybill: Arizona. Yeah, kind of the Four Corners region. And Uncle Hal, his herald, his firstborn child, talks about how they’d gone in there. They knew the Navajo were notorious for being horse thieves, so they set up their camp. They tie the horses to the tent lines, thinking, well, we’ll wake up if we hear anybody trying to do this.

So they go to sleep. They don’t hear anything. They get up the next morning, horses are all gone. And a couple of days later, a native starts making his way around their camp. And after a day or two of just kind of hanging out, he says he might know where the horses are for some money. And Curtis hands over a sack of coins. Hal says it was $150 worth, and gets his horses back.

[00:25:35] Coleen Graybill: Because they were miles back into Canyon de Chelly, which is really deep, loose sand.

[00:25:42] John Graybill: They were stuck.

[00:25:44] Coleen Graybill: They were stuck. Without horses.

[00:25:46] Adam Williams: I don’t think it would take much for people to figure out he’s walking around with bags of coin. That doesn’t feel safe around anybody.

[00:25:56] John Graybill: So back in the time, though, natives didn’t really need the currency. In fact, clear into 1927, he’s up in Alaska and he’s paying natives with silver coins. And one of the interpreters says, you’d be better off giving them a stick of chewing gum. It’d be more useful to them than your money. They just have no use for it.

[00:26:16] Adam Williams: I’m not even thinking necessarily of the tribes. It was– Yeah. If he’s on a train to get somewhere to the west to start a new adventure, or just anywhere to travel with bags of money. Now I’m picturing dollar signs, you know, painted on the burlap bag or something. It just seems like a precarious way to travel.

[00:26:38] Coleen Graybill: I’ve never read anything in all the letters and, of course, you know, stories and that he ever had any problems with people stealing the coins.

[00:26:51] Adam Williams: What really was the purpose of this work? Again, JP Morgan, if he’s backing him, at least for a period of time, was this to sell artwork? Almost like he’s this portrait photographer. People pay him. Was this a similar sort of thing for him? Or was it. If I think of someone like Ansel Adams, who would ultimately end up speaking to Congress and presenting some of his landscapes, and they had this influence with the most Powerful people in the nation.

Was Curtis’s work used in any similar way? Was it meant to be something that was more than just to wow the elites of the East Coast?

[00:27:32] Coleen Graybill: I think so. You know, kind of like Ansel Adams had that purpose of preserving the land, and if he could create these beautiful images, to use them as an emotional tool for Congress to save this land.

I think Curtis was in that same line of thinking that if he could show the beauty in these people, that people would understand them more and not be so discriminating to them.

And he was part of the Indian Welfare League. He started that group. And they would, you know, work for the benefit of laws and things to benefit Native rights. The Native rights, yeah.

[00:28:25] Adam Williams: So he genuinely cared.

[00:28:26] John Graybill: Yes, he did. And it’s like Coleen said early on, and it was a quote from the financial agreement meeting with JP Morgan. He says, I want to make them live forever. So he’d seen something with these people that went past just the beautiful pictures.

And his motivation was to capture everything he could about their way of life, their religion, their games, their government, what they ate, how they gathered, all of this. And that’s what’s in these volumes. And it’s amazing, the cultural reference that’s. That he documented in these volumes.

[00:29:06] Adam Williams: Coleen, when you said that, at first I thought, well, through photographs, what we’re doing is preserving legacy. We’re preserving at least awareness of a way of life and of these peoples. Do you also mean, John, that he maybe wanted to use those in a persuasive way that would maybe alter the. The intentions of, again, those in Washington or whoever had the strings of power to say, maybe we need to back and not try to ruin them. Maybe we need to allow them to live and have their own continued way of life.

[00:29:41] John Graybill: I think that had to have been part of his psyche in doing this work to commit the amount of time he did and the resources that he did. It was more than a profit center. In fact, he didn’t make any money on it. He didn’t get a dime from this project.

[00:29:59] Coleen Graybill: Everything he did make, he put back into the project.

[00:30:03] John Graybill: Yeah.

[00:30:03] Adam Williams: How did he care for his family?

[00:30:05] Coleen Graybill: That’s a good question.

[00:30:07] John Graybill: Well, he cared for him so well, his wife, Clara, divorces him.

[00:30:12] Adam Williams: They had several kids, right?

[00:30:13] John Graybill: He had four. Yes.

[00:30:15] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:30:16] John Graybill: Four children. Three girls and one boy. Yeah. So the stories that we’ve got that have been passed down, Curtis is out doing his work, and, you know, he’s gone as long as weather permits doing fieldwork, and when he’s done with that at the end of the year, during the winter season, he’s holed up in one of his cabins writing the volumes with his staff. So he’s just not around.

[00:30:42] Coleen Graybill: Or he’d be in New York trying to promote them or get them printed, or he’d be in the darkroom helping to make the images and decide on images.

[00:30:52] Adam Williams: So he wasn’t much of a dad either then, let’s say.

[00:30:54] Coleen Graybill: Well, his children adored him.

[00:30:57] Adam Williams: Were they excited by what he was doing?

[00:30:59] Coleen Graybill: Absolutely, yes.

[00:31:01] John Graybill: One of the things that we do know is when he’s out in the field. Clara was running the studio in Seattle. And was she also a photographer? She was not. But she’s running the studio. She’s not taking the photographs or darkroom. She’s like administrative management kind of thing. She has to answer all the collectors, and they’re beating down the door because he’s mortgaged everything. And everything that the studio produces financially goes to the project.

So she’s got to deal with all these collectors pounding on the door, wanting their money, and it gets ugly. And at one point, a couple years before they leave the Seattle area, his oldest daughter, my Aunt Beth, and her mom, get into a fight in the foyer of the studio. They’re, like, duking it out. So there was no love affair between the children and the mom, but there was with the dad.

They absolutely adored him, you know, and he takes three of his children into the field and on various trips. The fourth child, my Aunt Billy, she came along later, I think, what, 1909.

And Clara kept her from him. And it wasn’t until Clara died in 35 that Aunt Billy got to actually be with her dad and moved out west to be with the rest of the family.

[00:32:26] Adam Williams: How old would she have been at that time? You said 1935. And she was born in 1909.

[00:32:30] John Graybill: Yeah.

[00:32:31] Adam Williams: So she’s fully grown. I mean, she’s an adult woman. She’s an adult before she really gets to know her dad at all.

[00:32:36] John Graybill: Yes. And as soon as she does, she’s immersed in it, too. We’ve seen at least one manuscript that she was writing about her dad that she tried to get published but wasn’t able to get backing from what were.

[00:32:51] Adam Williams: In these volumes that he’s. 20 volumes, you’ve said?

[00:32:54] John Graybill: Yes.

[00:32:55] Adam Williams: That makes me think they’re thick. Lots of pages.

[00:32:58] John Graybill: Yes.

[00:32:59] Coleen Graybill: There’s just under 5,000 pages of text total throughout the. 20 volumes. Yeah.

[00:33:05] Adam Williams: So what’s in that? What is this? Is this some sort of narrative? Is this. When we say a volume, is it written for publication in the sense of, you know, telling this story, whether it was through documentation and it’s more of an expositional type writing, or was he trying to, you know, evoke emotion in the people who read it? What was this and what was its purpose?

[00:33:29] John Graybill: I don’t know that it was for evoking emotion, but that certainly comes out of this, you know, and pretty much for the most part, each chapter that talks about a separate tribe starts out about where they’re located, what their boundaries are. Yeah, what the boundaries are. And then what kind of structures they lived in, their homes, what did they gather for food, how did they hunt, what were their songs, their dance.

[00:34:00] Adam Williams: It’s anthropological.

[00:34:01] John Graybill: Absolutely, yes.

[00:34:03] Coleen Graybill: But written in a way that wasn’t so technical and type of writing, it was more that a normal person could understand what was being talked about. So it didn’t. It didn’t get real scientific. It was kept where a normal reader would read it and be interested.

[00:34:25] Adam Williams: Did these get printed and sold?

[00:34:28] John Graybill: They did. The original plan was to do 500 sets. So a set would be 20 volumes. And each volume had, I’m going to say, an average of 75 smaller photogravure prints in the volume.

And then in addition to that volume, there was a portfolio set that accompanied it. And that averaged probably about 35 larger prints for each of the 20 volumes.

[00:34:54] Adam Williams: Do you have any of that, any of the original?

[00:34:57] Coleen Graybill: The family collection has, yeah, quite a few.

[00:35:01] Adam Williams: Are there any others that you are aware of that still exist? Oh, yeah, absolutely. Smithsonian, at least I would hope.

[00:35:07] John Graybill: Absolutely. So he planned on 500 and best we can determine, he sold about 200. And the number is 222 subscriptions to these volumes. And these are libraries, museums and the ultra wealthy that would purchase these. He had another 50 copies printed and ready to be bound.

But the Great Depression hit at the end. They never got bound is all loose stuff. We’ve got a couple of those, minus all the photogravures, the high value stuff, but the text.

It’s kind of cool to see this unbound stuff. But anyway, so never got to the 500. It ran out of steam at the Great Depression and slips into oblivion.

[00:35:58] Coleen Graybill: So basically these are very rare books in the scheme of things.

[00:36:03] John Graybill: Some have been damaged through floods, fires, theft, all kinds of different things have reduced the amount that’s on there on our website, if your listeners are interested, we have a page for the Curtis census.

And this has been what, seven or eight year long project one of our board members has tackled with some substantial help of tracking down These volumes. And so they’ve documented what libraries, what.

[00:36:34] Coleen Graybill: Museums, or if it’s private collection.

[00:36:37] John Graybill: Yeah.

[00:36:38] Coleen Graybill: If it’s a full set or whether it’s only partial. And so it’s.

[00:36:44] John Graybill: There was an interesting thing. I did a talk just a few months ago back east and got to look at a set that a collector had recently come into possession of. It was set number 11. And through the census, we were able to go back and track. And so the first 25 sets went to JP Morgan, and then from there went to a library. And from there it got sold in auction, and this private collector ended up with it.

And so we shared that with this person so they could see where this whole set came from. It was kind of cool.

[00:37:21] Adam Williams: So the Great Depression puts a damper on the process of this stuff. Well, let me jump ahead here to the 70s, when it’s found in a Boston basement.

[00:37:31] John Graybill: Yes.

[00:37:32] Adam Williams: And that is part of what helps create a revival of awareness of his work. So that period of time between the 30s and the 70s, is that kind of just a dark period in terms of awareness of Edward Curtis’s work?

[00:37:46] John Graybill: A little bit. I mean, there was some awareness. I mean, it’s still in museums and libraries. And if we go back just a few years, it was 19– Well, Morgan dies, what, 1913 or something?

His son Jack takes over the empire. And in 1925, Jack comes to Curtis and says, we’re not seeing enough income from subscriptions. We need something other to help continue funding for you. We want all the copyrights. So Curtis signs over all of his copyrights, and any material goes to the Morgan empire.

1935, after everything’s all done, Charles Laureate, the bookstore owner in Boston, buys all this stuff from the Morgan Empire. The copper plates, all the glass plates, all the text, all the unbound stuff, all the prints. A ton of stuff.

[00:38:46] Coleen Graybill: For a thousand dollars?

[00:38:47] John Graybill: Yeah, for a thousand bucks. And so he rebinds some of the stuff. And I believe those. If you ever come across that they’re bound in blue leather, different than what Curtis was doing, which is more brown. And then Charles dies in 1937, two years later, and the bookstore kind of forgets about this stuff in the basement. And these college kids. Out of it was a group. Grandma Florence called them the Santa Fe Boys. But a group of them pulled money together, and somehow they knew about it or had seen it, and they offer.

I don’t know what it’s sold for, but they offer money, and they take in this entire possession. I think they saw the artistic value in the work when was this? 19– That would have been early 70s, that the Santa Fe boys find and purchase this treasure trove. And it’s at that time they start dispersing it because they see the artistic value in it.

[00:39:51] Coleen Graybill: They see the money in it.

[00:39:52] John Graybill: They see the money. And it wasn’t too long after that all kinds of art dealers, and probably some of the more prolific ones was Lois Fleury, downtown Seattle and Pioneer Square. Her and her husband see the value in this stuff.

And they have a gallery in downtown Seattle for years that sold and dealt in this material. And we’ve seen private collections that they help build for these private individuals. And it’s amazing.

[00:40:22] Adam Williams: This is part of the process, then, of why I know who Edward Curtis is in his work and why many would know. Otherwise it would have been, you know, as they say, relegated to the dustbin of history.

[00:40:35] John Graybill: Absolutely.

[00:40:36] Adam Williams: And I love that you can track through this different steps of some of this history, but it feels so sad to hear. Then that’s when it was dispersed, was when they got a hold of it out of this basement. So it became a rescue, and then it became this other thing that sent it all out in all these directions.

And now here you are trying to track it down with this census. And we’ll get to more of that here in a bit. I want to know, John, being a great grandson of Edward Curtis, was this something you grew up hearing about him, hearing about? Was there lore of this work and this man in the family? I don’t know that you strike me as old enough to have met and known him. So I wonder if you heard about him.

[00:41:22] John Graybill: Correct. I was born in 57 and he died in 52.

[00:41:26] Adam Williams: Okay.

[00:41:26] John Graybill: So I missed out on meeting him, but my dad met him. My dad had a relationship with his grandfather. And you would think with all this historical stuff, because my dad had a lot of stuff and we had a few pictures on the wall, you’d think that we heard stories galore.

My dad despised the art dealers that were profiting off of his grandfather’s work when his grandfather didn’t make a penny on it and died penniless. So my dad had a real thing, and that’s how I was brought up and raised. You don’t talk about it, you don’t promote it, you don’t make money off of it, you don’t sell it, none of that. So, I mean, it wasn’t until I’m out of college before I really start getting a hold on who Curtis was.

And that was very interesting to me. I think probably before my dad passed In January of 2019, I was able to show him or talk to him at least about. Even though the art dealers kind of broke apart the volumes and sets and sold it for money, it did help elevate the awareness of Curtis’s work. And that elevation came through his artistic value of the prints. I mean, some of these portraits are drop dead gorgeous.

And as a photographer trying to produce that in the field with natural light, no artificial light, I mean, how do you get Rembrandt lighting out in the field as often as he did? So he had techniques that we’d use. He used what they called a portrait tent from back in the day. It was rather large and it had a flap on the top of the tent that you can open it up. And that allowed him to get the right angle of light for the Rembrandt lighting.

[00:43:16] Adam Williams: And was it thin enough that it also could be used as a light box that would diffuse the sunlight when he was in direct sun.

[00:43:22] John Graybill: The pictures we’ve seen, it looks like it’s dark canvas. Heavy dark? No, no. Was it lighter?

[00:43:29] Coleen Graybill: Yeah.

[00:43:29] John Graybill: Okay, well.

[00:43:33] Coleen Graybill: Can you tell who studies the images?

[00:43:36] Adam Williams: I love it. I appreciate your help. John, you studied photography at Rhode Island School of Design, right?

[00:43:42] John Graybill: Not Rhode Island School of Design, but Rhode Island School of Photography.

[00:43:45] Adam Williams: Okay, okay.

[00:43:46] John Graybill: There is a difference.

[00:43:48] Adam Williams: I hear it now. Because RISD is a top notch art school, correct? Like it’s a well known name.

[00:43:56] John Graybill: Absolutely.

[00:43:57] Adam Williams: This was a separate school.

[00:43:58] John Graybill: Yes.

[00:43:59] Adam Williams: Okay. More importantly, that’s when you started learning about Edward Curtis. I assume you learned it as part of your education in photography.

[00:44:08] John Graybill: So there’s a funny story. I went to Ohio University as a fine art major with an under thing in photography. And to go on in the photography program you had to submit a portfolio.

And they don’t accept first portfolios, like for anybody. But I had this burning desire I have to do photography. When I got turned down there after my first year, that’s when I went to the Rhode Island School of Photography. So I’m at Ohio University, you know, and this was art history, like 101. It’s like an auditorium with 300 students in it, Right.

And over the holiday break at Christmas, we were to find or acquire an original piece of art and write a paper about it, composition and all this kind of stuff. And so I write back home, mom, I need a piece of original art. So she sends me a platinum print. A vanishing race, you know, like 11 by 14. Nowadays that print might go for, I don’t know, 50 or 60,000 bucks. And she sent it to me.

I write my paper, I turn in my paper and the print and I did well on it. And when I get it back, the professor says, okay, everybody’s stuff’s on a back table and it’s just piled on back there. But this is in the mid-70s and people aren’t aware enough of it yet or that thing would have disappeared, I’m sure. But I did get it back and.

[00:45:42] Coleen Graybill: Yeah, in a pile with paper clips and staples and.

[00:45:46] Adam Williams: Yeah, real artful care.

[00:45:49] John Graybill: Yeah.

[00:45:52] Adam Williams: Did your great grandfather’s work influence you in wanting to become a photographer?

[00:45:56] John Graybill: You know, that’s interesting. I get asked that a lot and I have to say yes. I think it was genetic memory that we’d moved from Southern California to Connecticut. I think that was 1966.

And I was playing around in the basement. I found this box of darkroom equipment and larger, some old film, a Brownie camera. And I said, dad, what is this? Well, that’s my stuff and well, can I use it? And so that was when I started doing photography and I was in the fifth grade and my fifth grade teacher said, hey, I’m going to be doing a after school class on black and white photography. Anybody interested? So I did that.

From that point forward, it was myopic point of view. I had to be a photographer. Nothing else mattered. Absolutely nothing.

[00:46:53] Adam Williams: Coleen, you also have a personal history with photography, right? You have worked as a portrait and fine art photographer for many years.

[00:47:01] Coleen Graybill: Yes.

[00:47:02] Adam Williams: Tell me about that. Where did that come from for you? Did you go to school for that? Or how did you get this. This career going that ultimately would lead you to be apparently the lead historian for the Curtis Legacy Foundation?

[00:47:15] Coleen Graybill: I like that answer.

[00:47:18] John Graybill: And she is.

[00:47:21] Coleen Graybill: My initial interest started in college. I had a roommate who was a journalism major, and she and one of our other roommates had taken a little road trip and. And she took a picture of our roommate sitting on a rock on the beach of Lake Michigan.

And just. She was just kind of playing in the water and the light was perfect coming in. It was, you know, that golden hour sunset. And it just, it gave me goosebumps because it portrayed who she was as a person. So well, it was just emotional. And that really triggered my interest in photography. So I started photographing when I did a lot of backpacking, backcountry kind of trips in college.

And so I started shooting there. But quickly the portrait interest came into view. After I moved to Colorado and I just started doing more and more portraits and their friends would start calling me So I built a business and did portraits and weddings for over 30 years and had a successful studio in Colorado Springs.

[00:48:43] Adam Williams: Is the focus for both of you now, the Curtis Legacy Foundation. That’s where you’re pouring your knowledge of photography and all of these things into it together.

[00:48:52] John Graybill: Yes.

[00:48:53] Adam Williams: I know that you two have been married. Is it eight years?

[00:48:57] Coleen Graybill: Yes.

[00:48:58] John Graybill: Has it been eight years already?

[00:49:02] Adam Williams: So, Coleen, I’m curious when you learned about Edward Curtis and his work, because it must have predated the two of you getting together and now your work that you’re doing for the foundation.

[00:49:14] Coleen Graybill: The first. The first time I met John, which was through a mutual photography friend of ours in Colorado Springs had kind of set us up and met him, and he mentioned Edward Curtis. And I’m like, name sounds kind of familiar.

Showed me some pictures and I’m like, yeah, I think those were in my history books. And then the first time I came to his house for dinner and he showed me his Curtis room, quote, unquote. And then I recognized the photographs more so. But I really had no idea who he was.

And shortly after we were married, I took a trip and decided I should probably read who this Edward Curtis is, because John had books all over the house. So I took one with me, and I was in Hook, Line and sinker, started reading a book by Timothy Egan called Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher.

And just the way he tells Curtis’s story, and I was calling him, like, every other hour. Did you know? Did you know? This is so cool. This is your great grandfather. And I was just so, so excited. And, yeah, then the ideas started flowing and things started happening. And here we are not. Not long after that, with books published on Curtis and traveling, giving presentations and doing exhibits.

[00:50:57] Adam Williams: And is it right that you were the impetus for the foundation? Is that true?

[00:51:02] Coleen Graybill: Yeah.

[00:51:03] Adam Williams: That you sparked this. You sparked the idea for this somehow?

[00:51:09] Coleen Graybill: Yeah. After we met, I closed down my portrait and wedding photography business. But I can’t sit still and do nothing and just be retired. It’s just not in my makeup. So, of course, all these things start running through my head. And he’s like, “yes, honey. Okay, honey.”

[00:51:31] John Graybill: There’s a piece that she left out earlier. Thank you. And the first time she comes over and I didn’t learn this till much later, she’s driving up to my cabin in the woods and she sees that cab and goes, oh, I might have to marry this guy. I didn’t learn that until after we.

[00:51:50] Coleen Graybill: Were married, many years after we married.

[00:51:54] Adam Williams: Well, I feel like she might be. Might be selling Short what the role there is, too, of her being the spark for the work that you two do now.

[00:52:02] John Graybill: Yeah. And so the one other piece I wanted to get to is she sees all this Curtis stuff on the walls in this one room, and she tells me, I think after we were married, she says, I was hoping you weren’t gonna hang any more Indian pictures on the walls.

And of course, then she reads Egan’s book, and now everything’s covered with pictures everywhere, which is kind of funny.

[00:52:25] Coleen Graybill: Yeah. It has become a deep passion, and I can’t let it go when I.

[00:52:35] John Graybill: Saw the struggles that she was going through doing her wedding business. And that is a hard business for anybody that’s never done it. That is hard work. That’s all day, nonstop.

[00:52:47] Coleen Graybill: Well, and that’s only a part of the work.

[00:52:50] John Graybill: That’s only the upfront part.

[00:52:51] Adam Williams: I’ve done some of it with my wife and can admit that I don’t like that.

[00:52:56] John Graybill: It’s hard.

[00:52:57] Adam Williams: It’s not for me.

[00:52:58] John Graybill: Yeah. Or for most people. And so I see her doing this. I said, honey, why don’t you stop that? And let’s just do landscape photography.

And we did. And, oh, my goodness, she was. She’s so good at that. I mean, she won international awards and. Amazing photographer. And so she gets me to join a Professional Photographer’s of America and an affiliate guild group for PPA in Colorado Springs. So we commute once a month over there, and we’re going to their meetings and having fun and all that kind of stuff.

And she talks to the president of the club, Jonathan Betts, and tells Jonathan who my great grandfather is. And Jonathan absolutely loves Curtis’s work. So he comes up and he says, john, you’re the great grandson. Yeah, John.

He says, would you give a presentation to the guild? I’m like, no, I don’t do public speaking. That’s not my thing. And I’ve still got this thing in my head about how my dad raised me. And so I leave it, and we get home, and Coleen says, well, you’ve got a date coming up in, like, a month and a half. You’re giving a talk. And so her and John had scheduled this, even though I said, no.

[00:54:17] Coleen Graybill: I’ll get him ready. He can do this.

[00:54:19] John Graybill: I’m, like, panicked, you know, because I didn’t grow up. No stories in the home, nothing. So I’m reading my great grandmother’s books and Tim Egan’s. I go through that again and Mick Gidley’s book and put this presentation together. I give the presentation and I get, like, a standing ovation.

People loved it. And I learned later that they’ve never had a standing ovation before. And so that was kind of cool. And I think it was. I call it the hot tub event. Maybe a week or two later, we’re out in the hot tub.

[00:54:57] Coleen Graybill: He’s giving you the side eye.

[00:54:58] Adam Williams: Oh, I’m just wondering where it’s going.

[00:55:01] John Graybill: And we’re talking about the presentation, how well it went, and it was actually enjoyable and fun. And then Coleen says, well, have you ever thought about finding descendants of the people that your great grandfather photographed and then photographing them now, today?

And it was that concept, that idea that kind of had to marinate for a while. But that was the genesis of the foundation, really. That was the impetus, and that was all Coleen.

And of course, like any good wife, she massages that for a while to make me think it was my idea, but it was not. It was hers.

[00:55:43] Adam Williams: Was it difficult to get over the hurdle of the intensity that your father felt against doing anything with this work and for you to say, no, let’s create this foundation. Let’s create our own creative project in the descendants project, which we’re going to talk about in a minute?

Yeah. Was that really difficult to say? I’m going to go against this lifelong teaching and story I’ve held from my dad and do something that advances Edward Curtis publicly.

[00:56:12] John Graybill: It was hard. And I look back, my Grandma Florence, out of the four children, she’s the one that really, her father inspired her. She idolized her dad and what he had accomplished. And she writes a couple of books in the early 70s about her dad.

She’s the one that would tell stories. And my sisters would talk about how they’d be sitting in the kitchen and people would be talking, and Grandma Florence would start in on her stories. And Janice says she’d roll her eyes back, oh, no, here comes another story from Grandma. It’s like, as young children, we were so deceptive, interested in that. So that was a little bit hard.

[00:56:57] Coleen Graybill: When we started forming these ideas. And John had given the presentation to the Guild in Colorado Springs, and he was going back to Washington state to visit his family. I don’t remember why he was going without me, but he went back and he gave the presentation that he had done for Guild to his family.

So it was mom, dad, and both sisters. So the whole family was there. And so he gave the presentation. And I said, you need approval from especially your father for us to move forward or we’re not going to do anything. But I Would love it if your whole family was good with this. And so he talked to them, and his father gave the blessing for us to move forward and to the idea of not only bringing Curtis work up and continuing that legacy per the family, but to continue Curtis mission of bringing native voices.

And so we wanted, through our descendants project, to lift up natives of today and let’s hear their stories from today.

[00:58:22] John Graybill: Kind of like what Grandma Florence did. I mean, she was big about promoting her father and talked all across the country, on the west coast at least, plus the two books. And so she was elevating her father the best she could. And any proceeds that she got from her book sales, she gave back to Native communities.

So she wasn’t profiting off of that. And that was kind of the same stance that we took. We didn’t. What we were looking at doing wasn’t for monetary gain. I’d retired from my professional career, you know, a modest savings account. But that’s what we live on. And we don’t make any money for our own personal gain from what we do. It all goes back into the foundation. And through our Give Back program, we help support various things in Native communities.

[00:59:13] Adam Williams: For those of you who feel like, those of you in the family who feel like this is really worth promoting, and you’ve mentioned, you know, writing books and the things that others have done. I wonder how you all see him and why that is sort of a personal mission and you feel like I need to advance what my father did, what my grandfather, what my great grandfather did.

You know, I can look at him and say, this was a famous photographer from this particular era. This is a historical figure. He’s somebody that, in terms of photography, I mentioned Ansel Adams, Matthew Brady from the Civil War, and you have Edward Curtis in what he did in documenting and making portraits of indigenous peoples in a certain era. I guess I just wonder why you. Why you try to advance this work.

Like, what is the passion behind that and why you feel like it’s worthy of that versus well, it’s just what he did. That was. It came, it went. That’s it. Like most of us, our careers, they come, they go. There’s nobody who’s going to carry on a legacy for us. Why is this legacy worthy in a way? I don’t ask that critically. I ask that curiously.

John Graybill: Yeah, and that’s a great question. And, you know, it goes back to a lot of people ask us, what was Curtis’ motivation? Although we have nothing in writing, I believe he saw something in these people that was different than the colonists of the day. He saw people, a beautiful people, a beautiful culture that was very deep.

And for us, it’s not the art that we’re trying to promote. It’s the text that he wrote and that he saved for future generations. And even to this day, there are tribes that go back and refer to what he wrote to reestablish old cultural ways. He’s got some amazing stuff documented in there. Weddings, for example.

One of our descendants from up in Vancouver Island, Andy Everson, he shared in the interview how he and his wife, when they got married, they wanted to decolonize the ceremony.

The tribal elders didn’t retain enough of the information to put all that together, so they referred back to what Curtis wrote in the volumes. And so the material is still used today for. For very legitimate, productive reasons for the native culture.

[01:01:50] Adam Williams: That’s amazing. They did not know how to decolonize their own customs they had. Because it had been lost.

[01:01:57] John Graybill: Yeah, exactly. And that’s what Curtis said right from the start. I want to make him live forever. And to some extent, the tribes that he did come in contact with, he’s done that.

You know, there’s like. For Crow, he talks about in the volume about the sacred tobacco society and the process that they would go through, the ritualistic process of planting the seeds.

And recently, some Crow natives had contacted me and say, they don’t harvest, they don’t plant the seeds. There’s still a sacred tobacco society, but they don’t do anything and they’ve lost their tobacco.

And so an elder had gotten seeds from a sister tribe up north in Canada, which was where we believe the Crow Nation tobacco originally came from. Anyway, gave me some seeds. John, would you try growing these? So I grew them and I harvested them. I gave them the tobacco and the seeds back.

And this elder Crow native was so inspired by having the sacred tobacco. And I mean, we did the whole thing. We had natives that came and did ceremony and prayed through the whole process of me growing this stuff. He was so excited. He took this tobacco, and like, two days after he’s got it, he’s having ceremony up in cronation with this tobacco. And it inspired him. So it’s reinvigorated him. It’s given him a new spark and purpose. And he wants to take the whole tribe back into cultural ways from this experience of revisiting the old ways of the tobacco society.

So it’s all these little things about these people and their culture that are fascinating to me. I don’t have that in my white culture. Nothing like what they have. And it’s a beautiful thing. It’s deeply spiritual. And it’s because of that that I do what I do, what the foundation does.

[01:04:01] Adam Williams: What is the mission of the foundation? Briefly?

[01:04:07] John Graybill: I’m talking a lot. You can chime in if you want.

[01:04:11] Coleen Graybill: For those only listening who are giving each other the eyeball. Our mission is to lift Native voices of today through using Curtis work to open that door.

So, say, for instance, you know, museums that want to do an exhibit, they hear Edward Curtis’s name and they’re like, yeah, you guys should come and do some presentations and talks and do an exhibit. And we’re like, yeah, but we’re going to bring these Native people with us, and we’re going to let them tell their story. It’s important to us to let them.

[01:04:52] Adam Williams: I think that’s often the risk for us as white folks.

[01:04:54] John Graybill: Right.

[01:04:54] Adam Williams: Is if we are taking the role of savior of anybody else and trying to tell their story for them or represent for them, instead of maybe being a bridge that creates opportunity where possible, and then empowers them to share what they have to share because it’s their story.

[01:05:13] John Graybill: Right, Absolutely.

[01:05:14] Coleen Graybill: Yeah.

[01:05:15] John Graybill: Spot on.

[01:05:16] Coleen Graybill: And there’s times when that’s not feasible to bring in people just monetarily. We could use more donations on that note, so that we could take various speakers, native speakers, with us more. My preference would be to always have someone there. And I just think it’s really important. And they are so.

It’s like every person that we’ve come in contact in the Native American world is just so elegant and eloquent, and you’re just listening so deeply when they speak because they just say it so differently and from such a different point of view. And I can’t begin to say it like they do. And so the more we can have them speak, the more we’re meeting our mission because their stories are amazing and they’re so deep and just culturally informative and awakening. I can’t begin to describe it unless you hear it.

[01:06:38] Adam Williams: And people can. Who are listening, can hear some of what you’re doing. Right. Because of this Descendants project, you not only photograph descendants of those who Edward Curtis photographed, you interview them on video, and then There is a YouTube channel where people can watch and listen.

[01:06:55] Coleen Graybill: Yes.

[01:06:56] Adam Williams: To descendants of these people. Right. So you’ve taken it another step that Edward Curtis wasn’t able to. To do in that way at the time.

[01:07:05] Coleen Graybill: Right.

[01:07:06] John Graybill: That I think is amazing was the technology they had available. I mean, he. He had an old silent movie Camera that he took and made videos of. And then he had the Edison wax cylinder recorder that he recorded their song on.

[01:07:22] Adam Williams: I have never heard of this before. Not. Not in his work.

[01:07:26] Coleen Graybill: Not a lot of the wax cylinders are. Are left.

[01:07:31] John Graybill: Yeah. Again, that was one of those odd things he said. Well, he recorded 10,000 wax cylinder recordings, like the 40,000 pictures. Okay, I. I’m not so sure about that number. But there’s like. The number I want to say is 276 still remain. They’re at the University of Indiana in Bloomington. They’ve been digitized.

[01:07:55] Adam Williams: Wow. Is there a way that we could access them and be able to listen to what he recorded?

[01:07:59] John Graybill: You gotta be native.

[01:08:01] Adam Williams: Okay.

[01:08:01] Coleen Graybill: Native Americans have access to their songs, but the rest of us do not.

[01:08:07] Adam Williams: Okay, so it’s not for general consumption, like, as content would be the word we’d use today. It was strictly preservation of the culture and customs.

[01:08:19] Coleen Graybill: There has been some used in some very large museum exhibits on Curtis where.

[01:08:27] John Graybill: They’Ve gotten permission to.

[01:08:28] Coleen Graybill: They have to get permission from either the tribe or the family that these songs came from. Some of them are sacred songs, so they shouldn’t be played for general public. Some are very personal family songs.

[01:08:44] Adam Williams: How about the silent films? Are those also there?

[01:08:47] Coleen Graybill: There’s not a lot of those.

[01:08:49] John Graybill: I don’t know where that stuff’s at. We see clips here and there. The thing that I always fall back on is film. Back in the day, unless it was his glass plates was a cellulose nitrate backing. And that stuff was highly volatile, like spontaneous combustion. At 80 degrees and 50% humidity, they could just go poof. And it’s what burnt movie houses down in the early days of silent movies. It’s that stuff, crazy unsafe stuff. And if it didn’t explode, it turned into this gooey pile of stuff that’s just a mess. So unless it’s properly preserved, that just doesn’t exist anymore, sadly.

[01:09:36] Coleen Graybill: We just acquired a photograph from the Smithsonian of Edward and his son Hal with this big movie camera and this other guy sitting in, like, a director’s chair with a megaphone next to him and a couple other people. And it’s like, I don’t know what he was filming or where he was by the looks of it. I think it’s Canada. But it’s like, what film is this? Where is it?

[01:10:07] Adam Williams: Does this stuff deepen the mystery in terms of continuing that fire to collect, find things, find where they are? The census on the materials just kind of keep motivating you to continue the work that you’re doing in that way.

[01:10:23] John Graybill: Absolutely.

[01:10:23] Adam Williams: Do you feel like you’re the keeper, John, especially. But both of you, obviously, of this legacy. And, you know, it could have again, fallen to a basement somewhere maybe if this wasn’t the work that you were doing.

[01:10:37] Coleen Graybill: Right now it’s spread out so much between private collectors and museums and–

[01:10:46] Adam Williams: But none of them are advancing it in the same way that I think you have the interest.

[01:10:51] John Graybill: Exactly. And I-

[01:10:53] Coleen Graybill: But they’re not. Yeah. Advancing it. That’s.

[01:10:56] Adam Williams: And you’re extending it. You’re extending it through the descendants, which I want to hear more about that, you know, before we keep letting that slide be. Because that, to me is. Is so amazing that you are tracking down who these people were. There’s one, I think her name is Anna, who is in a video, who was a toddler in a photograph of a family portrait that Edward Curtis made. And you have since found her. Met, talked, and I assume made a portrait of her.

[01:11:26] John Graybill: Absolutely. You know, and she’s not really a descendant in the true sense of what we’re talking about.

[01:11:33] Coleen Graybill: She’s the actual person.

[01:11:34] John Graybill: She was the actual person.

[01:11:35] Adam Williams: Right.

[01:11:35] John Graybill: Curtis photograph, which, you know, she was three years old in 1927 when Curtis photographed her his last field season. And we stumble upon this person. All this stuff just for the most part, just happens and falls in our lap.

Like there’s some other larger purpose there that brings these people to us. But we got to interview her and photograph her. We had her here in town when we did the exhibit at the Heritage Museum for unpublished Alaska. She came, she talked. People would ask her questions.

[01:12:14] Adam Williams: She’s 100 years old now.

[01:12:16] John Graybill: She’s passed now.

[01:12:17] Coleen Graybill: She passed about a year and a half ago at 99.

[01:12:20] Adam Williams: Okay.

[01:12:21] Coleen Graybill: Yeah.

[01:12:21] Adam Williams: But she was traveling, making that effort at a very advanced age.

[01:12:25] Coleen Graybill: It sounds like she was 94 when she came over here.

[01:12:27] Adam Williams: Okay.

[01:12:27] John Graybill: Yeah. Yes. Just amazing. It gives me goosebumps today to think about photographing the same person Great Gramps photographed.

[01:12:37] Coleen Graybill: And she remembered him because he didn’t dress like they did. So his appearance was very different. He had blue eyes, which she remembered distinct.

[01:12:49] Adam Williams: So he would have been a real rarity in her life to have ever appeared as this white man who showed up completely an outsider and obviously so tall.

[01:12:57] Coleen Graybill: Yeah.

[01:12:57] John Graybill: Yeah.

[01:12:58] Adam Williams: When you are working with descendants, then what are we saying? Are they typically great grandchildren? Grandchildren of those who. Who Curtis photographed?

[01:13:08] John Graybill: Yeah, great-grandchildren. Great-great grandchildren. A lot of them are probably five generations out.

[01:13:17] Coleen Graybill: It’s kind of the average, I would say, is five generations.

[01:13:21] Adam Williams: How do they receive you when the two of you come in for this project, and you’re obviously a descendant of that man who then they have probably some awareness of on some level.

I imagine that helps in terms of the advance, you know, door opening, just like Curtis would have had someone help with that when he needed it. Does that help make that easier? And the fact that you both are descendants then also is a common point to just sort of, I don’t know, look at each other and just say, wow, this is weird.

[01:13:54] John Graybill: Yeah, we had that exact experience that you’re talking about with Henry Red Cloud out on Pine Ridge, and we.

After we had done our initial interview and photographed Henry, which is a fascinating story, about a year later, he gives me a call and says, john, would you and Coleen come up for my making of a chief ceremony?

So we head up there, and the night before the big ceremony, Chief Henry Red Cloud is there. Chief John Spotted Tail is there. Their wives are there. We’re there. And this is on the Rosebud Reservation. And we all kind of look at each in South Dakota. Yeah.

And we’re looking at each other and say, you know, all of our ancestors were together in this area, too. And it gave us all goosebumps to put it in that kind of a context, where some hundred years previously, they were all together. And since then, the families haven’t exchanged anything. We didn’t even know of each other. And then this happens. This is, like, crazy.

[01:15:02] Coleen Graybill: Well, in one of our first descendant that John photographed, who we’d talked about, Princess Angeline before, Chief Seattle’s daughter, the first time we met her, I mean, we walked in the door, and there was just this obvious instant bond between John and Mary Lou. And They felt it. They felt that historical bond between them.

[01:15:35] John Graybill: And there’s more to that story than just that.

[01:15:39] Coleen Graybill: Well, she kept asking me if I, if I was sure I was married. She wanted to. She wanted to marry him. [01:15:48] John Graybill: That’s not where I was going with it, but that is funny. That was hilarious.

[01:15:52] Coleen Graybill: You know, she was 80 at the time.

[01:15:53] John Graybill: She’s in her 80s, and she’s whispering in my ear, will Coleen share you? And that kind of stuff. But that’s not where I was going with it.

We put my parents in assisted living, and through conversation with them, they let us know that they’re no longer taking phone calls for people asking for information about Curtis. And I’d never known that my parents were doing this, but after the fact, I find my dad was really helpful to people working on postgraduate degrees and Studying Curtis and doing. He would help those people any way he could. Art dealers? No, but in the education world he would.

And you know, so we go on and I said, well, dad, rather than hanging up on those people, why don’t you just send them to me? Because we starting on this project and all. I’m happy to answer their questions. The very first call we get is from Vaughn Raymond out of Seattle, who’s producing a documentary for Curtis’s 150th birth celebration in Seattle. And it was a town wide event.

And he’s telling us about all the different places he’ll take us. Where Curtis was, where his studio was, the Rainier Club. And so he said, yeah, this sounds good, let’s go do this. So we’re doing this. And through conversation he learns about our Descendants project, which was just in the conceptional phase. And Vaughn says, you know, I might be able to introduce you to somebody. The great, great, great granddaughter of Princess Angeline. Okay, we’ll do this. And so we go out there and, and turns out she’s my first work with a native.

[01:17:44] Adam Williams: Okay, that was Edward Curtis’s first was Princess Angeline.

[01:17:49] John Graybill: And then her descendant was my first.

[01:17:52] Adam Williams: There’s so much serendipity in so many of these encounters. It feels like in just the way you’ve described the way it all just kind of keeps coming to you, falling into place. That’s amazing.

[01:18:02] John Graybill: There’s greater power behind all this, I believe.

[01:18:06] Coleen Graybill: Like Anna, the, the child that Curtis photographed. And then we photographed, we found her from Joe and Kimmy Randall, who are local photographers here. And we were having a conversation with them one day and talking about our project. And they were like that, that’s my friend’s grandma. And I’m like, what?

And she’s like, and she lives in Colorado Springs. I’m like, what? Yeah, so that’s how we ended up meeting Anna was through Joe and Kimmy.

[01:18:40] Adam Williams: How many people have you seen, interviewed, photographed? You know, as part of this Descendants.

[01:18:46] John Graybill: Project, we’re at 28 currently. And the initial goal was to do 30. And 30 was completely arbitrary, but we thought that might make a nice sized book to produce material from and exhibit. And it will, and that’s what we’re going with. But since then we’ve realized, well, we meet so many interesting people that aren’t necessarily descendants, but they’re important figures in today’s world.

And so probably when this phase of the Descendants project is done, we’ll continue some other phase of it working with descendants and other non descendants.

Just creating a slice in time from today of what their lives are like for future generations. And I always position it with them. I said, okay, when you come dressed for your portrait, come dressed as you want to be remembered seven generations from now.

And that’s how they come dressed however they want to be portrayed and looked back upon in this time from their future generations.

[01:19:49] Coleen Graybill: So we’ve had everything from ball caps and blue jeans to full out chief regalia and everything in between. And it just depends on the person and how much they live their culture or don’t.

[01:20:09] John Graybill: That’s part of the story too.

[01:20:10] Coleen Graybill: Run the whole gamut. And then next month John’s going to be going back down to Arizona to Canyon De Chelly.

So one of Curtis’s most famous image is titled Canyon de Chelly. And it’s these seven riders going through the base of the canyon. And the descendant’s family were the writers in that photograph. And so that’s going to be a really cool interview. And we’ve met him and he’s a park ranger for Canyon de Chelly and also at liaison between the park and the Navajo tribe. So he’s going to be a fascinating interview.

[01:20:53] Adam Williams: I think it all sounds fascinating.

[01:20:55] John Graybill: It is.

[01:20:56] Adam Williams: I think, you know, I almost get chills and I’m not the one related. Thinking of being able to connect with some of these descendants who are in these sometimes famous like you’re saying the Canyon de Chelly photograph of those riders and to be able to connect all These years later, 100 years, give or take.

[01:21:16] Coleen Graybill: Right.

[01:21:17] Adam Williams: It would just be, I think an amazing thing and it’s very cool what you’re doing with this work.

Speaking of that, Coleen, one of the big roles you have with the Curtis Legacy foundation is with the unpublished works. You’re putting together books. There are a couple already published and a third one that people can pre order for.

And what do you want us to know about that? What, what is the distinction between these books and anything you want to tell us about how you gather these unpublished works from Curtis to continue to, to, you know, extend that legacy into the world?

[01:21:53] Coleen Graybill: Yeah, it’s Covid’s fault. So when Covid hit, we actually had four descendants lined up for April of that spring to go out and do and obviously everything got canceled and shut down. And after a week or two I was going stir crazy. And so I looked back on some of Anna’s family who had looked through some of the notebooks that we have, just reprints of Curtis’s work from negatives and knowing that there were some images that we had that hadn’t ever been published.

So I started comparing and realized, okay, Alaska is going to be the easiest for me to determine one, because they were all in these two particular notebooks. And Alaska Natives have a much different look than the rest of the United States. So that one was an easy one for me to start with. So we found 200 images that had not been published before. I narrowed it down to 100 because there was kind of some duplication or it was like a second shot of the same thing. And so we published that book along with Curtis and his daughter Beth’s journals from that trip. And reading those journals, we don’t know how they survived.

It was quite a treacherous journey for them to visit the places they did in a 40 foot boat on the Bering Sea and, you know, getting caught in ice, getting blown up on sand shoals, and not being able to move for days. And so that was an exciting story.